In the Studio: Samira Abbassy

“My attempt in depicting the human form is almost like a psychic x-ray, so the n...

Javier Orfón is an artist who lives and works between San Lorenzo and Caguas, Puerto Rico. He is a 2023 Joan Mitchell Fellow. We interviewed him about his work and creative practice in January 2024. The following is a translated and edited transcript of that conversation. Descarga la traducción al español aquí.

I work mainly with sculpture and drawing, and most of my practice is focused on how to combine these mediums to create installations in which I incorporate found materials sourced from specific places that I study over time. It is through the interaction with these spaces that I explore that I select the appropriate materials to convey the idea I want to carry out.

When I arrive at a specific space, I learn about its importance not only because of its natural significance, but also because of the historical human presence. Every time I visit, it's a learning experience. By specific space, I mean a place like a natural reserve, where there is also community interaction with the people who live nearby. I also include research from scientists who have conducted studies at the site. I arrive at many of these spaces thanks to these scientific studies, but also through literary references from artists or writers who mention them as having served as inspiration for their different creations.

I also try to work on the place’s phenomenology, doing research on what the experience was like there, and that leads me to learn about context and discover the materials it has to offer. I then use those materials to develop an artistic project.

A constant reference in my work ever since my years as a student has been the use of concrete poetry. In college I learned about it and about the play between the written and the visual. I also learned about the work of the Puerto Rican poet and conceptual artist Esteban Valdés, from which I began to explore this medium in more depth. I read a lot of poetry and I love to translate it into visual language. I also wanted to understand the world from the Caribbean standpoint, understand my place in the world. I’ve been inspired by specific poems and how I could use them as a visual language, to learn more about my archipelago and the Caribbean, and thus understand the world. Esteban's work has been very influential for many fellow artists and writers in Puerto Rico. Recently Marina Reyes managed a project to print another edition of his book Fuera de Trabajo.

Another big influence on my work has been the artist and craftswoman Alice Cheveres, my teacher. She is from the town of Morovis, and her work focuses on the recreation and preparation of traditional pottery, as it was done in the Caribbean islands many years ago. I learned from Alice how to prepare clay and about our traditions and our history. Alongside her, I was able to appreciate the oral traditions both in her workshop and in the surrounding area of the Cabachuelas natural reserve—knowledge that continues in our culture and goes beyond academic parameters. I came to realize that there is a lot of mythology and knowledge that has been around for a long time. I have been able to learn about many places in the Caribbean, and poetically understand my place here.

The project titled Bientevéo, which was included in the Whitney Museum's exhibition, no existe un mundo poshuracán, is a research-based work that originated in the Guajataca forest located in the northwest of Puerto Rico. Between 2018 and 2021, I interacted with this natural reserve and took many references: notes, photos, samples of plant life. I also walked along the trails with René, the ranger, and with my colleague Steve Maldonado, an amateur ethnobotanist, and interviewed the amateur botanist, Papo Vives, to learn more about the forest. I love this forest because of how quiet it is.

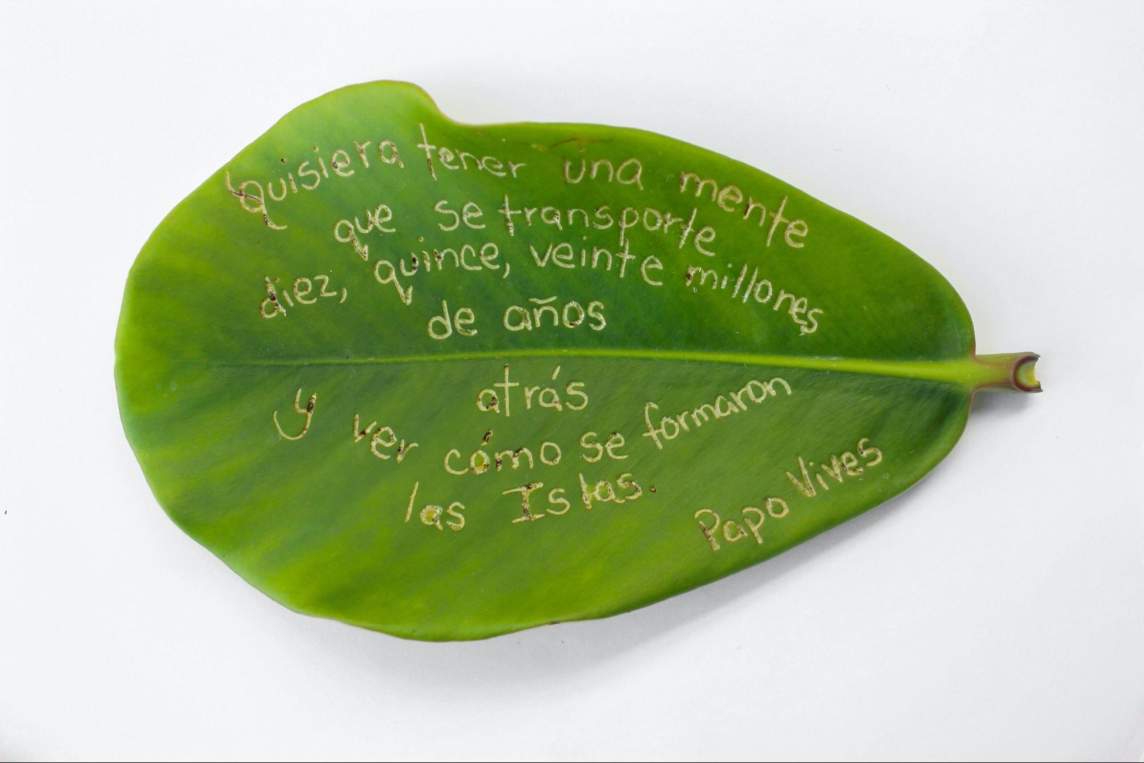

Through this research process, I realized how important this forest is and learned about the beings that only live there. I really like scientific illustration and wanted to do that as a reference, but using a very common material such as the leaves of the cupey tree, a type of tropical Ficus from the Caribbean.

The cupey has a very hard leaf, which was used by the first Europeans to arrive in the Caribbean to write. Many people who visit the forest leave their drawings or their names on the leaves. They are very durable leaves. So, during my walks I collected the leaves and the thorns that I found, which I later used to make a series of drawings of the things I heard during these hikes, of the people around me or the animals I saw, details of events that I could appreciate. I also took photos of plants that are unique to the area.

The Bientevéo series is made up of nine photographs of the drawings I made on cupey leaves and two that are native plants from the natural reserve, or from the region. The installation was conceived to suggest the shape of the Ficus, the cupey tree, seen on the cliffs of the Mogote Mountains, which are limestone mountains in the Karst region of northern Puerto Rico. The title of the project, Bientevéo, references a bird that is native to this forest, and also a compound Spanish word that translates to, “I see you well.”

I recently worked on Mona Island, located on the western end of the Puerto Rico archipelago, thanks to the invitation of the writer Karina del Valle Shorke. I spent six intense days in the natural reserve and took many references from what I saw—plants and animals, but also traces of the human presence in this area. I was able to see many pictographs, petroglyphs, the impact of guano extraction and of the military presence on the island, which is full of caves. Let's say it is like a giant sponge that has many intestines or tubes.

Using liquid paper and fragments of found granite, I made a concrete poem with drawings and letters inspired by this whole experience. This work has the shape of the island, which resembles a heart, and also alludes to what the island is: an immense, colossal stone, full of stories, inhabited by beings that are unique to this area.

More recently, I have been working in the southwest region of Puerto Rico. I moved into an apartment there, with the aim of working in the dry forest of Guánica and carrying out my project El astrolabio del Guabairo. And I have been interacting with the place, walking along the paths during both the day and night, to make poetic movements, thinking about how I can poetically present the geography of the place, but also the sky. This forest is in the region of Puerto Rico with the least light pollution, and I have been learning how to use my telescope and taking reference photographs of everything I have been observing.

Among my current projects is the exhibition La piedra vulnerable [The Vulnerable Stone] at Hidrante gallery, in which I am going to present a ceramic piece that relates to my experiences as a speleologist—or a cave aficionado—and a work inspired by those visits. In March presented my piece Bientevéo at the ARCO Madrid fair, with the Ana Mas Projects gallery.

I really like to work in installation because I can refer to or recreate the experience that I had in a specific place, and then through the medium of installation, translate this experience for the viewer to feel or witness. A while ago, I saw an interview with the artist Beatriz Santiago Muñoz, and she made me wonder why I make art. What for? This is a question from which I start to make art: How can I, through my artistic work, create something interesting for the viewer? This is why I'm also very careful when selecting the material. I love that it has a certain poetry to it.

Interview and editing by Jenny Gill and Solana Chehtman; editing and translation by Mariana Barrera Pieck. Learn more about Javier Orfón’s work here and on Instagram.

Download interview in Spanish / Descarga la traducción al español aquí.