Ryan Wong

Ryan Lee Wong is a writer and arts organizer based in Brooklyn. He advises Joan Mitchell Foundation grant recipients and artists-in-residence on writing and digital communications. Learn more about his work at ryanleewong.com.

Ryan Wong

Ryan Wong is a writer and arts organizer who consults with Joan Mitchell Foundation grant recipients as part of our ongoing Professional Development series. We asked Ryan to share insights for artists gained from his research on artist collectives.

In an art world that shines light on individuals, and where the work of organizing is often unpaid and under-recognized, why form an artist collective?

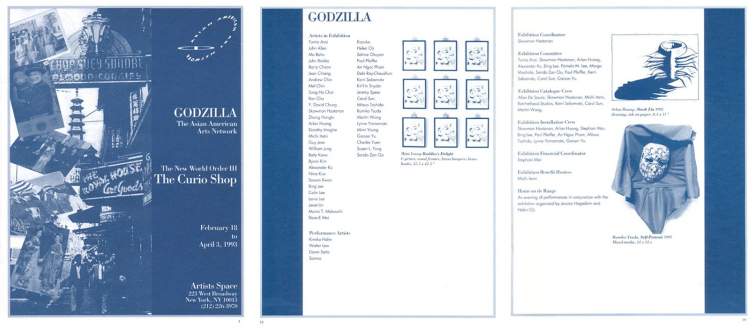

I’m organizing an exhibition on Godzilla: Asian American Arts Network, a creative and dynamic group from the 1990s that influenced a generation of artists and shifted the story of American art. The co-curator, Herb Tam, is Curator and Director of Exhibitions at Museum of Chinese in America, which will host the exhibition in spring of 2020.

Godzilla connected artists and curators directly, allowing them to support each other in a white-dominated art world that often ignored or misunderstood them. Their tactics included a newsletter, multiple exhibitions, slide slams, and social events, addressing artists’ needs from different angles.

Today, a score of younger Asian American groups, from Yellow Jackets Collective to AN/Other New York, are again building support and community outside institutions. Clearly, artists still feel a need to collectivize. By looking back at Godzilla, we can find concrete reasons one might create, join, and work with a collective.

To form an artistic community.

Godzilla began out of need. Artist and Godzilla member Arlan Huang, reflecting on his years of activism and art practice, says, "My whole life there have always been two roads: the community art road and the mainstream art world road. And I have never been able to integrate them as one. Godzilla was a good attempt at that."

Before it even had a name, a “Tuesday Lunch Club” including the artists Bing Lee and Ken Chu and curator and writer Margo Machida would meet, usually in Chinatown, and usually somewhere cheap. The three then gathered to hatch an organization. They made an intentional choice not to be a 501(c)(3), and not to institute membership dues. While some members note that this made fundraising and organizing hard, it also meant they never had much of the administrative and fundraising work of non-profits. The group, even as it expanded, remained open and artist-centered.

To build strength within the art world.

Co-Founder Ken Chu recalls assembling the Godzilla newsletters and being surprised by the multiple pages they filled with listings of exhibitions featuring Asian American artists. “We, as well as other arts professionals, were impressed with the extent of our engagement in contemporary arts. No one knew.” That is, the work of Asian American artists was already robust, but until Godzilla no one had gathered them.

In 1991, Godzilla wrote an open letter to David Ross, the director of the Whitney Museum, noting the lack of Asian American artists in the last Biennial. Ross and the Whitney responded by inviting several members to a meeting, and to send in slides of Asian American artists. The landmark 1993 Biennial included the work of Godzilla member Byron Kim; Eugenie Tsai, another Godzilla member, became a curator at the Whitney soon after, and showed other Godzilla members there. Just as importantly, Godzilla showed the Whitney that there was an organized community holding it accountable.

To make a different kind of work possible.

In 1993, Godzilla members co-organized the exhibition A New World Order III: The Curio Shop at Artists Space, a subversion of the Chinatown curio shops that catered to tourists. The artist Skowmon Hastanan, who helped organize the exhibition, recalls that the show’s idea, and the fact that it wasn’t ‘curated,’ pushed artists to “freely create or share subjects that turned out to be more personal or emotional than their usual work.” Artists were encouraged to turn towards subjects like war, orientalism, displacement, and sexuality—personal topics they might not have addressed directly before. By offering a radically open, Asian American-centered space, Godzilla freed its members to experiment, to be more vulnerable in their work.

To sustain artists.

Ken Chu recalls participating in many overlapping activist organizations like APICHA, GAPIMNY, and ACT-UP and “seeing a high burnout rate.” As with other artists of color, many Asian American artists doubled as arts professionals. Chu wanted a space that would “sustain our community—where we can share information and resources, to not replicate but build on each other’s work in the various arts organizations and the field.” By intentionally making an alternative type of organization, perhaps Godzilla could support and lengthen artists’ careers.

Almost every Godzilla member we’ve talked to is still making art. It’s impossible to say, of course, how much that can be credited to Godzilla. But there’s no doubt it helped. Some artists recall having transformative studio visits with other Godzilla members. Others remember Godzilla more for its social aspect: parties, meals, and peer encouragement. Others focus on the projects and exhibitions Godzilla did: from the Curio Shop to Urban Encounters at the New Museum in 1998 to their final street banner installation on Canal Street with Art in General in 2001.

I’m moved to meet so many artists who have, against the odds, found ways to keep making work during the thirty years since the group’s founding. If Godzilla played some role in this collective dedication, it succeeded.

Related resources: