In the Studio: Samira Abbassy

“My attempt in depicting the human form is almost like a psychic x-ray, so the n...

Victoria Burge is an artist based in New Hampshire, and a 2024 Joan Mitchell Fellow. We interviewed Burge about her work and creative practice in February 2025.

I make works on paper and small sculptures. In my practice, I study graphic notation through different contexts and histories—most recently in the fields of astronomy and weaving. I’m interested in how close looking and visual translation animates objects and narratives from the past.

An underlying principle of my work is a focus on process that I began cultivating during my training as a printmaker. Alongside this training, I volunteered in the book conservation department at the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia, making archival enclosures and small repairs to the diaries of 19th century explorers. I now make frequent visits to archives and special collection libraries as an integral step in the development of new projects. Predating my formal education was my upbringing in my grandparent’s art gallery on the Upper East Side of Manhattan in the 1980s. This formative experience instilled in me a lasting fascination with the world of objects, mark making, and visual languages.

In our digital world with rapidly developing Artificial Intelligence, I honor the slow pace, the unpredictable rhythm, of both the analog machine and the object made by hand. An inevitable element of delight when working within archives and special collection libraries is discovering an unexpected object within the pages of a book. These relics—often folded papers haphazardly tucked into the back of a notebook or stuffed between signatures—create a moment of intimate connection with the long-ago author. They may be deeply flattened from time and pressure, and frequently contain a sketch, symbol, sentence, or code. These graphic traces are the artifacts that inspire me.

My studio is located in a textile mill building situated within a small rural village in southern New Hampshire. The village is one of many water-powered mill towns that developed in New England in the early 19th century, but it is the only one that has largely survived in its original form. My studio sits above the river that runs through the mill building that once powered the mill. The energy of the fast-moving water and the building’s history of making is a palpable presence within my space.

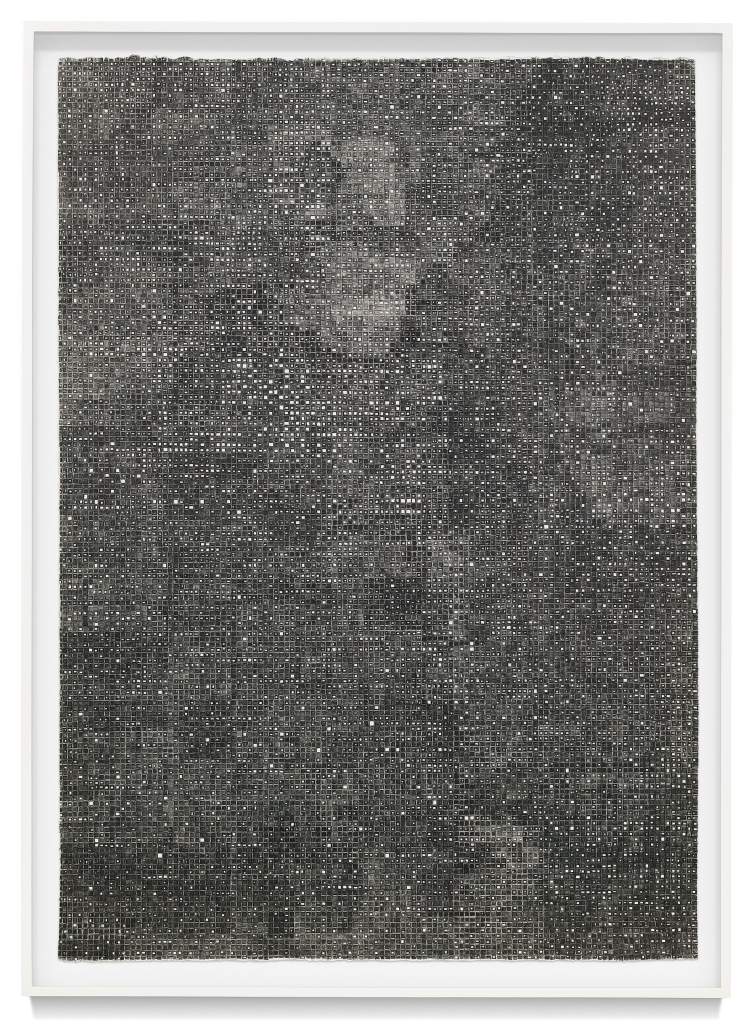

For the past few years, I have been working with the grid and thinking about how it relates to structure and systems, its role within art history, its relationship to abstraction.

Joan Retallack, in her paper “Geometries of Attention,” writes: “This is what geometries do—they organize the vectors of our attention, establish relations between abstract directionalities, insides and outsides, enabling us to notice certain things we could not otherwise.”

The grid organizes the vectors of my attention. I think of it as a geometric form; a stabilizing, reliable framework that helps me enter a drawing. It is within this infrastructure that organization or disorganization can take shape.

I also think of the grid as a finding tool, a guide. Its boundaries give me a constraint in which to work. Because I love repetition, its static composition offers me the same place to start from again and again. I am a slow maker. The grid helps me track my pace within a drawing, serving as a reliable marker of magnification, focus, distance, and time.

As Christopher Alessandrini wrote in a recent review of my work, “The grid is often unfairly associated with a specific strain of Minimalist machismo, though the radical compositions of Anni Albers, Beryl Korot, Agnes Martin, and Vera Molnar attest to its malleability and emotional range…In her own effort to humanize the grid, [Burge] stages moments of strategic breakdown, puncturing the illusion or expectation of perfection.”

I love the tension of the perceived flaw within a manuscript, a notebook, or an artwork: a line that runs too far, a smudge, or the ghostly presence of an erasure. Such errors are manifestations of beauty and offer a moment of interference; a pause; an energy.

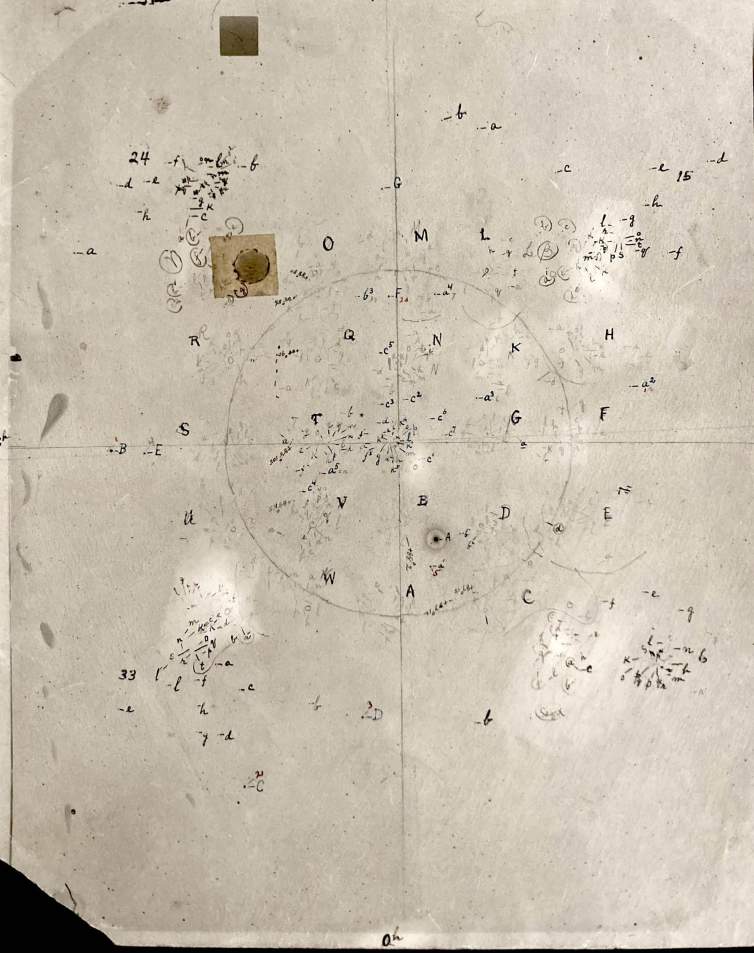

Since 2022, I have been working with two very different archives. The first is the archive of the Harvard Computers (women astronomers) at The Harvard College Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The second is an eclectic collection of weaving manuscripts, primarily from the 19th century, at Cooper Hewitt’s textile department in New York. I have been looking at, among other things, how the astronomer and the textile maker use the grid to navigate, compose, and record information.

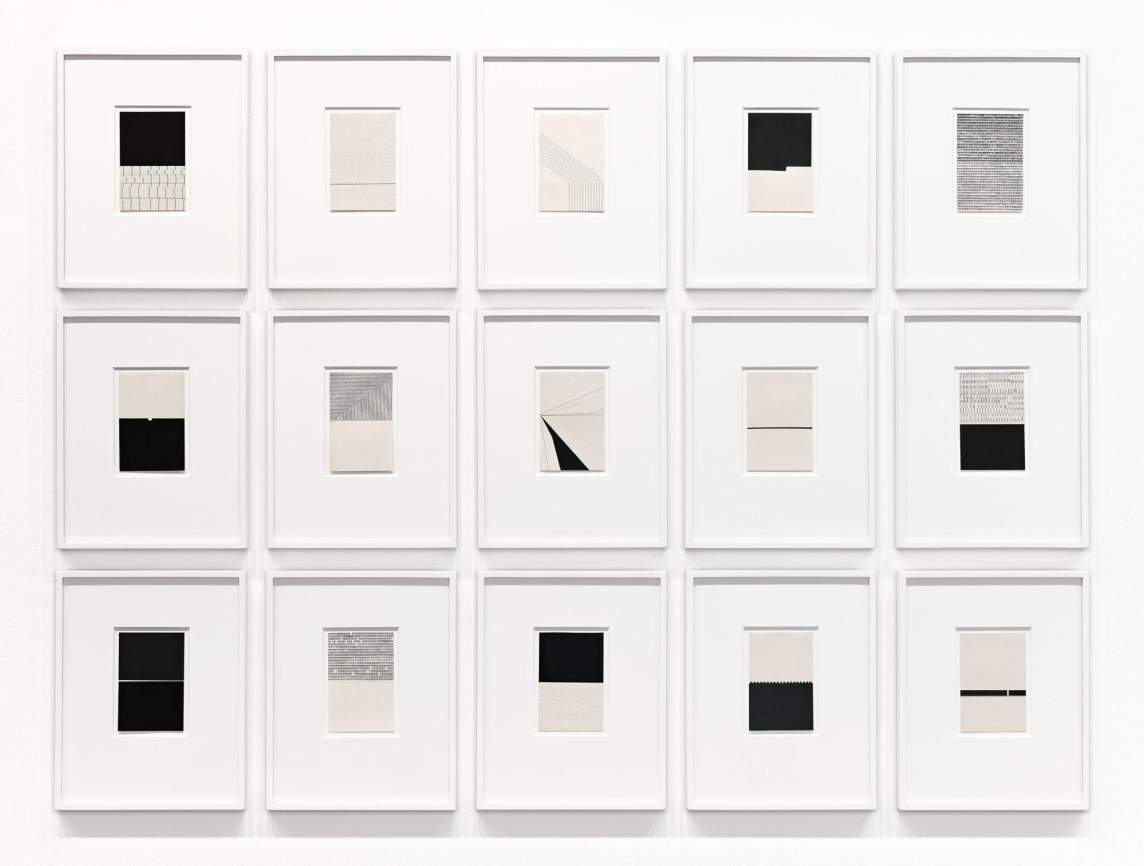

In response to these two collections, I have been making artworks that resemble small archives: indices of visual notes, folded structures, and patterns. I have been exhibiting these artworks in curated groups to suggest the unpacking of objects from an archive – holding, opening, turning pages, and laying out pieces of ephemera, letters, notebooks. The physicality of handling these items is an intimate act. Drawing in response to them becomes a cipher, a new way into this information.

While making these works, I have been thinking about the accessibility and importance of tangible data; the idea of the handwritten notation existing as both a drawing and a vestige of seen/unseen labor. Materially, I have been thinking about the structural capacity and endurance of paper. How a creased line, for example, can activate a paper’s surface sculpturally.

I just opened a solo show, and my studio is now empty of work. After focusing for two years on making a family of related pieces, the anticipation of starting anew is dizzying and grounding.

Last week, I ordered some big sheets of paper and will begin working on a series of large-scale drawings. I work slowly, without assistants, so time and the physicality of making are concepts that are ever present for me in my studio.

To find my way into these new drawings, I will be working with a collection of photographs shared with me by a colleague. The images are of water droplets left on spider webs after a long rain last summer, captured with a macro lens on her mobile phone. They are jewel-like constellations of light and links.

I don’t yet know where these images will lead me, but they encompass so many things that I have been thinking about in my work: codes, diagrams, patterns. Observation and close-looking. The myths of weavers and stars. Labor. The seen; unseen. The role of the grid as an infrastructure. The simple weighted beauty of a line, a space.

Interview and editing by Jenny Gill. Learn more about Victoria Burge’s work at victoriaburge.com.