In the Studio: Samira Abbassy

“My attempt in depicting the human form is almost like a psychic x-ray, so the n...

Scott Hocking is a Detroit-based artist and 2022 Joan Mitchell Fellow. We interviewed him about his work in March 2023. The following is an edited transcript of that conversation.

I like to say that I'm a site-specific installation artist, but the truth is that I do photography, I make videos, I do sculptures, and I make sculptural installations. Sometimes all of those things combine or intersect. The one thing I don't typically do is paintings. But I like to create artwork based on whatever medium seems right for that idea. If it seems like an idea needs to manifest through an interpretative dance, maybe it will. I haven't done that yet, but if there's a chance out there, I want to be open to that.

I really like working with the history of a place, the energy of a place, the feeling I get there, ideas from the people I talk to, the books I read, the news, ancient history—anything. I’m interested in combining layers of history together with a location and the materials that are available—or sometimes not available, but ideally I like to use already available wasted materials, so that I can work with that energy and history, and recycle things that already exist instead of making more waste. I'm always setting myself up for the challenge of figuring out a new way of working for each project, and I kind of love that challenge.

In reality, I'm sketching with sculpting. I'm figuring it out as I go. I'm moving by feel. Like a lot of artists, I always want to wait for that lightning-strike of inspiration and clarity of vision. You don't always have that luxury time-wise, but I think you can find ways to get there more urgently if you need to. For me, it's all about adaptability. I feel like being an artist is all about navigating through obstacles in every project. It's an ongoing series of juxtapositions. Like if I'm doing a crazy giant sculptural installation where it's physically taxing, taking on some kind of Sisyphean task, that’s usually when I'm thinking, "Man, I wish I could just do a series of tiny drawings on napkins." Or, "I need to start making sculptures that are like two inches tall, made out of lightweight materials."

Mentally, I work on multiple ideas and parallel projects all the time. For instance, right now, I have a few public sculptures that I’m moving forward and I’m making work for an upcoming solo show for Central Michigan University. I've got probably TOO many ongoing Detroit-based photo series that I basically "work" on every time I get in my car. And I’m continuing work on kayak-based projects in Detroit and Michigan, filming and documenting from the waterways. I think that maybe working in different mediums is a balancing act that's helpful to keep my whole life balanced. I can find respite in other mediums when I'm sick of one. I might want to do all of them in the end, but during the hard parts, switching gears is often my way to get through the challenges.

As you get older and keep working, you can start to see the timeline of your work and a bird's eye view of it all, and say, "Oh, I've been talking about this or that the whole time!” I think that I'm always using art to work through my own trauma, my own patterns in life. I'm using it to interpret what the hell's going on in the world. And one of the main threads in my practice is that I get irritated with the patterns of human behavior on Earth, the dumb shit we've done over and over again, and that we continue to do. Abandoning and wasting material, leaving trails of destruction wherever we go. It fuels me, makes me want to comment on it, to do something about it. I don't necessarily think it changes anything in the long run, but I do feel driven by that.

I'm also interested in using wasted material to talk about deeper, more universal and metaphysical ideas, like cycles of death and rebirth, and how we perceive decay, death, and endings. Are there really any endings? Or are we just a part of the natural cycle that keeps eternally moving in patterns of birth and life and death and rebirth? Aren't we a part of that? Not only in our own personal lives, but in the bigger timelines of human history, the planetary cycles, the macro and micro universes, etc. I’m interested in these same patterns in civilizations, in mythologies, in history, religion, and mysticism.

There are also really practical throughlines in my work. I come from a very working class background. I learned how to use tools when I was very young, and I come from a city that is very famously industrial. Everybody somehow has a connection to the auto industry or cars in Detroit. I grew up next to the train tracks, and in almost every project I do, I throw in some materials or connections to the railroad, sometimes even as just an Easter egg for myself. It’s in my blood. The railroad was a solace for me when I was young. I would go to the tracks and walk there and explore, escaping reality for a bit. There are many ideas like this that keep threading through my projects, and maybe I'm still trying to hash them out as I keep working over the years.

In August of last year, I installed an 11-foot bronze sculpture in downtown Detroit called Floating Citadel. It's the biggest public sculpture that I've ever made in a metropolis. This is central to the city, it's permanent, and it's going to outlast us. If there was a cataclysmic apocalyptic event, it would stick out of the ground like the Statue of Liberty in Planet of the Apes. I feel pretty good about that, and the piece in general. It was important for me career-wise, but it was also a bit of a self-portrait that I've been making versions of since 1999. My sewer grate rib cage self-portrait. I decided to make a bunch of smaller versions out of bronze as well, so for the last two semesters, I've been working at the art school here in Detroit, using their foundry to make smaller bronze works.

Right now, I’m in the early stages of a project that I’ll be doing in Bosnia & Herzegovina. In May, I'm being brought to Bosnia by curator Irfan Hošić, who wants me to do a site-specific intervention, installation, possibly permanent piece. I'm very intrigued with the concrete sculptures and monuments all throughout former Yugoslavia, called Spomeniks. They're in various states of decay, a lot of them are reinforced cast concrete or stone, and very Brutalist in form. I’m looking forward to this trip. I'll learn a lot of history, then I'll come back to Detroit and I'll figure out what the hell I'm going to do.

Research is a big part of my practice—just sitting in front of the computer, going down rabbit holes, reading and learning. And if there's a direction I'll follow it. It might not take me anywhere, it might be a dead end, but to me, it's a huge part of what I do: learning, filtering, deciphering. You know, people in Detroit get very sensitive about outsiders coming in to do projects and having some hot take on the history here, only to leave two weeks later. So, I don't ever want to be that guy when I do projects outside of where I live and work. That's a big part of the research for me. I want to know, from Bosnians, is this a good idea, or do you think this is a full of shit direction? All of it helps inform me and guides my work.

I just de-installed a 25-year retrospective exhibition at Cranbrook Art Museum. It was really humbling. I rarely feel proud and I don’t really like to have an ego about this stuff. I try to focus on the work, focus on the ideas, the process. But I actually did feel proud. I felt like, "Holy shit, I'm still alive, I'm less broke than I've ever been, and somebody out there has decided that I'm worthy of having a major exhibition at a museum.” It was really mind-blowing.

Of course, like a lot of my projects, the install was a major physical undertaking. There were multiple large-scale installations in the museum, along with photographs documenting site-specific projects that can't be recreated. But the install went smoothly. That was a bit shocking, too. I'm so used to there being some wrenches thrown in the works. I think that part of the experience was seeing that I'm really good at navigating around these obstacles, just moving through them. On the day of the opening, I wasn't stressed, which was nice.

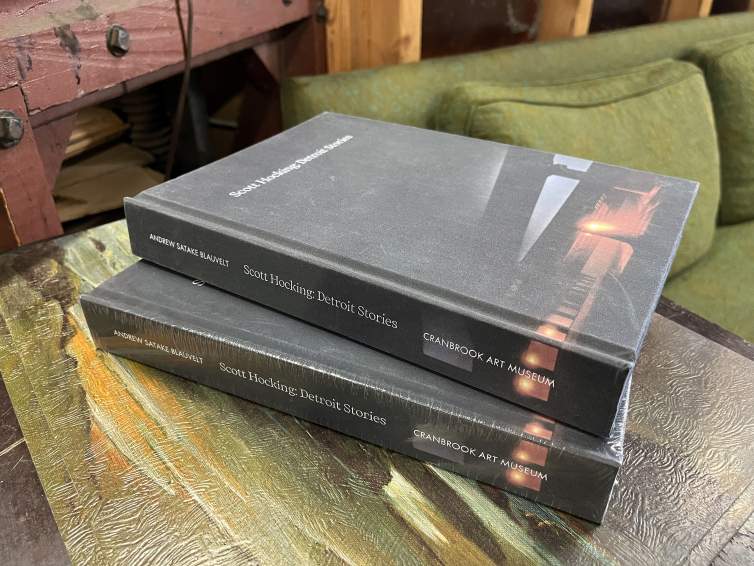

Prior to installing the show, I also spent a huge amount of time working on the catalog. Andrew Blauvelt, the Director of Cranbrook Art Museum and curator of my retrospective, really researched the crap out of me and my practice when putting together the exhibition. He scoured my website, read articles, followed long-winded Instagram stories I'd written… It was impressive. And it was his idea to focus on my writing, in addition to all the artwork in the exhibition, and to create a comprehensive catalog for the show. If you couldn't tell already from this interview, I can really spin a yarn! So it makes a lot of sense that Andrew decided to call my retrospective Detroit Stories.

In the end, we worked together on the 344-page tome for about 6 months. It features 12 essays of mine—some long, some short, some from almost 20 years ago, and some written specifically for the catalog. In addition, I wrote descriptions for all 44 projects included in the catalog. There were also placards of my writing through the exhibit, excerpts from the texts. So many people came up after and said how much they enjoyed reading those. That aspect was, again, very surprising, and it gave me this feeling that, moving forward, I do want to keep focusing on integrating writing into things I do. Not that I hadn't already, but this really formalized it and put a stamp on it and made it feel official.

There was a bit of a feeling with this retrospective, like, "Maybe this is it. Maybe that's the pinnacle. I reached it, I did it. I had a museum retrospective. It's all downhill from here.” Who knows? But I'm okay with that, by the way. When you're an artist, you get used to living with uncertainty. I think, in a way, most artists did fine during COVID because we were like, "Oh, this is how we always live, with the unknown.” I'm okay with this. I chose to live with the unknown, not knowing where the next paycheck was coming from or if the world was going to end tomorrow.

And also with the retrospective, there was a feeling like, “You keep working. You keep busting your ass. You keep focusing on your ideas, and things happen.” It's heartening. It changes some of that unknown to a certainty. And makes me feel that I didn't make a wrong choice when I decided to go that direction decades ago. I've been following a path, and I'm going to keep doing that and seeing what happens. And winning the Joan Mitchell Fellowship was one of those moments where you go, "Oh, shit! I'm going to keep getting paid for years!” Meaning, I'm definitely still going to be an artist years from now.

Interview and editing by Jenny Gill. Learn more about Scott Hocking’s work here.