In the Studio: Samira Abbassy

“My attempt in depicting the human form is almost like a psychic x-ray, so the n...

Rose B. Simpson is an artist from New Mexico and a 2021 recipient of the Joan Mitchell Fellowship. We interviewed her about her work and studio practice in June 2022. The following is an edited transcript of that conversation.

My work is research into a very personal space, into my relationship to process and to a spiritual or psychological journey. The objects are the result or the by-product of that investigation. It’s what comes from the journey. These things are kind of like the wake of it, that can ideally go out into the world and help other people, maybe, in their own investigation, their own journeys.

I'm really attached to clay because the way that it records emotion is way more immediate, I think, than other forms or materials. I also work with metal and cars and wood and those are very different kinds of relationships. Metal is so architectural and, in a way, cerebral. And wood is an extractive process, so you're grinding and carving. Clay is so very much about feeling, so it's about building and investing something with meaning and form. It’s about growing itself rather than deleting to become. And it records your emotional state instantly. The water molecules in the clay itself are hearing your intention much more than a more dense material like metal.

When I was working with wood last year, I was thinking so much about gratitude for the resources that give their lives for us to do what we do every day, like plants and animals that die to feed us. But also, the wood is so much this being and you're in direct relationship with its body, its being, and there's this constant humbleness and gratitude that you have to be in, which I think is a whole other state.

Clay is like the body of our mother. And when you work with it, it's not the end of it. You take clay from the earth and you build with it and you fire it. It's vitrified, so it’s a rock, and it'll crumble back down and be reused. It's still a part of this wave of being, so it's still ephemeral in a way.

I work with the vessel. And the vessel—whether it's a car or an abstracted figure—it's a vessel for intention. I think that human figures as a type of vessel for intention get the biggest empathic response because we see ourselves in the figure and we are all about relationships.

I've been thinking so much about the idea of inanimate and animate. I really believe that when we see something as inanimate and not holding life within it, we objectify it. And when we objectify it, we can use and extract. And so by giving something life, when you give it animation, in a sense, it has meaning and you have to confront it and listen to it without judging it. I think the best way to do that is with the human figure, because we're better at that. And if it's abstract enough, then we can see it as ourselves and an emotional aspect of ourselves, which makes it even more easy to have an empathic response from it. It’s a difficult balance. If it's too specific, we can “other” it, right? And if it's too abstract, it might not necessarily build an empathic response.

My hope is that it represents a spiritual or psychological aspect of ourselves or something that we're yearning for or searching for within ourselves. As I look for those places within myself, I find them, I illustrate them. Because we are all one, we are seeing a part of ourselves in the other. So that's sort of the idea. If I can identify this part of myself, I'm doing that on behalf of all, and others who see it might see themselves in it and can grow as well.

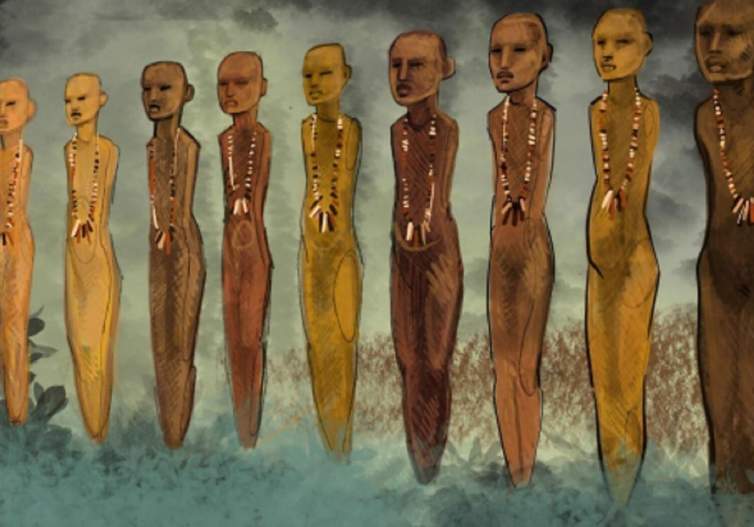

I am about to go to Williamstown, Massachusetts, to install 12 nine-foot-tall figures at a place called Field Farm. I made the originals in wood and they have been cast with colored cement, which is the first time in my life I have collaborated or had someone else sort of reproduce my work. It was a whole other way of working where my hand isn't necessarily in it because I carved the figures with a chainsaw, so they're different from my clay beings. We’re going to go install all 12 of these in the field. In that specific location is the Stockbridge-Munsee Band of Mohicans that have been relocated to Wisconsin, and we're going to be sourcing local clay from the area and then taking it to their community and we'll be making beads for the sculptures, so they’ll have these handmade bead necklaces.

These figures stand to represent the ancestry and the relationship of ancestral people to place, as a reminder of that and as an animation of history, of memory, of accountability. This piece is going to travel, and I'm hoping to build relationships with the different communities that these pieces travel to and they'll get new necklaces. So there will be these chapters, in a sense, of story and place. It's been a big growth for me to do this piece, because it's a collaboration with the fabricators and it's a collaboration with different tribes and places. And it's monumental.

I also have a big show at the Fabric Workshop and Museum coming up in the fall and that's really, really exciting. We're building a dream house. So it’s a series of spaces. Some are accessible by the audience, some aren't, and they represent parts of my journey and my internal investigations sort of visually. It's really, really exciting because I feel like, as people walk through this, they're going to understand my process way more than any words can explain, and hopefully they can be ushered into new parts of their own psyche through the experience. We're building furniture, we're making pillows, we're doing all kinds of cool stuff that I don't get to do generally. We’re making pottery—one of the rooms is like a kitchen so it's going to have nice cups and bowls and stuff.

I also have a solo show at the Boston ICA in August, so I've been getting ready for that. They're bringing up work from the past five years. I work in different ways, so it has been cool to see all the work together and think about how I can highlight the different styles of my work and also the constant investigation I have.

There’s a piece where I was thinking about guidance and where you find it. I use star imagery often, so it's that we are guided, that we have faith and guidance. And then I use this X, which is protection. So we're protected and directed.

Then, these are these figures that are hugging like a horse. It’s two pieces that have no feet so they're balanced on these two points. They look funny right now like they're in an argument, but they actually fit together on their necks so they lean together. They're led by their hearts. It’s called “Brace.”

There’s a figure that I'm tying a lot of pots onto. She's going to have like 24 pots hanging off of her. As I'm working, I pinch some more pots and I'll throw those in the kiln and then they will get tied onto her.

I also have some car projects that I’m working on. That’s fun. I have a show car, Maria, she is a 1985 Chevy El Camino that I started making in 2012. I went to school for automotive science and auto body in our town, which is basically low-rider school. And I purchased the El Camino for a performance piece that I did at the Denver Art Museum while I was a resident there. The idea was around building a power object that sort of deconstructed gender roles and became a source of strength and power for the performers in these spaces. So, it again relates to the idea of a vessel, and my long relationship and codependency with vehicles.

My town, Española, is the low-rider capital of the world. There's more custom cars per capita than Orange County or Vegas. I bought my first car when I was 12. Cars have been really important to me in my life as a psychological tool and manifestation of my own capability and my independence. Understanding an engine and how it works is very empowering. I think it has to do with men, relationships to men, and being able to fix your own car. Like, “I don't need anybody, I can do it myself.”

The performances that I have done I call transformances because you put this adornment on and transform your identity and you enter into a space with a different consciousness of being. The car was also a part of that. It was a method or a tool, a way to reach that sort of empowered state or that transformation inside yourself. It comes from growing up in a town where the cruise line was so important—where you cruise through town and you would have a sense of strength and power and identity that felt enlightened. And a higher vibration.

I named Maria after Maria Martinez, who was a really important person in our Tewa community. She was from another Tewa speaking tribe, San Ildefonso, which is directly south of our tribe. And she and her partner were some of the first to develop a certain style of pottery, which was black on black. She would polish her red clay pottery to a super shine with stone and grease, and then they would paint a slip over that to create like a matte. And then it'd be fired in a deep carbon reduction to be black, a very rich black.

That style became incredibly important in this area. My tribe's style is a little different. We do black-on-black, but it has a sort of a deep incision from Santa Clara Pueblo. But because of the nature of the car and the flatness of the surface, I painted her with the Maria Martinez style of black on black, and I named her Maria.

Maria is an El Camino, and she has a GM A-body, which is a flagship of Chicano low-rider culture. We're in this long conversation on colonization and co-habitating—sharing space and learning to live together with the Hispanic population of this area. I am from Santa Clara Pueblo, but I also grew up in the Hispanic, low-rider culture of Española. It’s an aesthetic I admire and I found strength in as a teenager. And that’s why I built this car as a conversation around place, around empowerment, around aesthetics and what that looks like as a vessel. She's a truck; we used her to harvest the fields. And I keep learning from her. She keeps teaching me.

In a sense, Maria's never finished. I just replaced her carburetor a few weeks ago and she just broke down, so I think she needs a new clutch and transmission. I put a huge engine in her—she has a 410 horsepower 350 with a Tremec drag race transmission. So she's really not a low-rider, she's actually a street rod. She's really fast and loud. She sounds like an airplane and she’s not happy until she's going 110 miles an hour. That's why she's always breaking down, because she doesn't want to just sit there and overheat. She wants to be nuking through the world.

My daughter doesn’t like to ride in her because she’s sick of breaking down. One day, we were cruising and Maria was overheating so we were on the side of the road waiting for her to cool off, and my daughter was like, "Mom, how come we don't have a bouncy car? They go all slow and then they have fun. They're not passing everybody. They're going super slow on two wheels. That's what I want." And I looked at her and was like, "That's what's up, kid!"

So I'm working on a new car project, a '64 Buick Riviera that's going to have hydraulics. I'm really excited about this car having a very detailed interior and not worrying about the exterior. She has this amazing patina from time that I think I'm going to leave, because it’s a collaboration with the atmosphere. But on the inside, I want to sew an entire leather constellation on the ceiling and the seats, and everything will be incredibly detailed and fabulous. So the whole point is about going slow and cruising and sitting on two wheels, and it’s about a focus on the internal and less about what everybody on the outside thinks of you.

I also have a '69 El Camino, which is lifted, so she has these swamper tires that are like three feet tall, they're huge. She’s got a straight-six engine, which is a 292, so it'll have a lot of low end torque. I’ve just got to find the transmission that'll fit with four-wheel drive, because with four-wheel drive you can take it to the mountains. And I'm really excited about this car just being rugged, because Maria is so perfect, you can't scratch her and you've got to kind of baby her all the time. I call her Mad Maxine and it’s going to be full-on Mad Max style. It's my apocalypse mobile, like the zombie killer.

So, you need to get all your bases covered. You have a low rider, a street rod, a rat rod—you never know what you might be feeling that day. And that comes full circle back to relational aesthetics and the transformation of our aesthetic decisions on the daily. It's like when you wake up in the morning and you choose what shirt you're going to wear. Every aesthetic decision can be a method of self love or awareness. And when we have more agency in that choice—like, “okay, this is who I want to be, this is how I want to feel”—then you are becoming more empowered.

It goes back to Indigenous aesthetics. There's no separation between art and life and there's no separation between spirit and art and spirituality and religious belief systems. All those things are connected. I'm coming from a perspective where of course this is all related. Every single thing you do is prayer. And to be more conscious of it, you're more empowered in the prayer that you're bringing to your life.

Interview and editing by Jenny Gill. Learn more about Rose B. Simpson’s work at rosebsimpson.com.