In the Studio: Samira Abbassy

“My attempt in depicting the human form is almost like a psychic x-ray, so the n...

Emilie Louise Gossiaux is a multidisciplinary artist based in New York City, and a 2024 Joan Mitchell Fellow. We interviewed her about her work and creative practice in March 2025. The following is excerpted and edited from a transcript of that conversation.

I am mainly a sculptor. I make ceramics and installation work, and drawing is a really big part of my practice, too. Drawing has always been an entry point for me, and a meditative process, where I envision a blank piece of paper that's in my hands. I feel it out, and that's when the images start to come. I start to visualize what it is that I am seeing in my mind.

Eventually that sketch or that drawing gets translated into something three-dimensional—a sculpture or an installation or a bigger drawing. I can work on the same image over and over and over again until it starts to feel real.

All my work for the past five years has been about this profound connection that I have with London, my guide dog and animal companion, who is an English Labrador retriever. I got London in 2013. She has been retired as my guide dog for the past three years. We've been together for over a decade, so this feels like the longest relationship I've had with another being.

This strong feeling of connection with London really started to sink in around 2017 or 2018. It can take a few years for a guide dog and their person to become super bonded with each other. It's a relationship that isn't like any other between an animal and a human, I think. It's stronger than a pet. Really, it's kind of radical to think about putting so much dependency on an animal, who is also 100% dependent on you. I describe it as an interdependent relationship, which means that we're mutually dependent on each other. To put that much care into someone, and for them to put their life on the line for me—it's just a beautiful thing. It's really powerful.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, London and I were both stuck at home and kind of trying to figure things out, since London wasn't really working during that period as my guide dog. We were just home together all the time. I couldn't really go out on my own. That was when I started to think about not just my relationship with London, but also other animals and other parts of nature and the environment that are so vital and important to us as human beings, and the responsibility we have to nature and non-human species. This interdependent relationship that I'm exploring through London is true for the rest of the world—humanity and the non-human world as well.

I was thinking about hierarchies that are in place between humans and animals, and also between humans and disabled people. I started thinking, how can I de-center humans? My desire is to create an anti-anthropocentric world where humans and animals are able to coexist between species, and also between genders and disabilities and race. I feel like a lot of people really take that for granted.

Through working with London, who has been a big time collaborator and such a huge part of my life, one of the things I want my audience to take away is this greater significance that animals can play in our lives, and also how nature and this idea of interdependency are so vital to our existence.

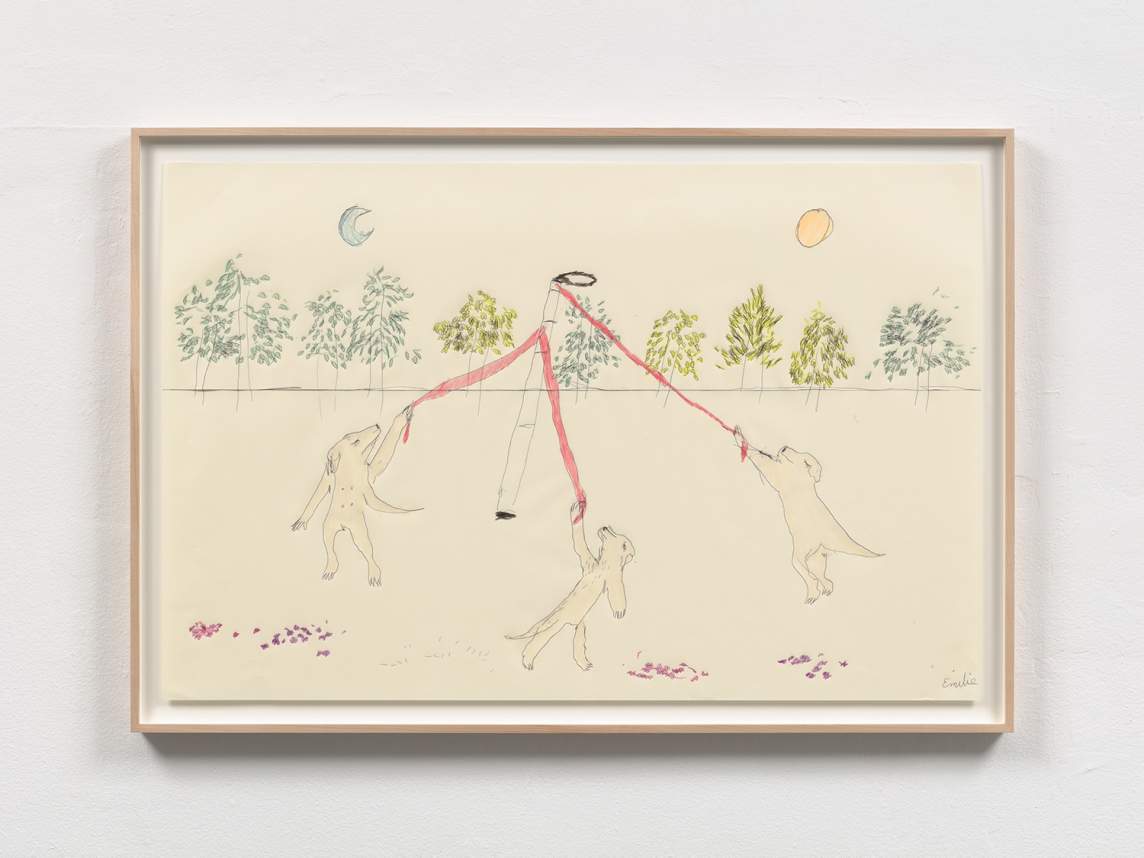

In 2023, I had a solo exhibition Other-Worlding at the Queens Museum that explored this theme. It started with a proposal, an idea, which originated with my drawing London Midsummer, which I drew in 2022. There were three representations of London, standing in a field surrounded by trees with a giant maypole that I modeled to resemble my white cane. She's standing upright on her hind legs and holding onto her dog leashes, which are these red ribbons that are attached to the top of the maypole. And she's dancing and skipping around it.

When I made that drawing, I felt like I had to explore this idea of animal liberation, joy, and Disability autonomy further and to figure out how to make it into an installation. The gallery where the show was at the Queens Museum is a large space, and so working at that scale, it became a world-building process, because I feel like my sketches can be really fantastical and imaginative and very dreamlike or surreal. I wanted the installation to be immersive, and for my audience to be able to enter this world that I created where dogs are dancing upright on their hind legs in the middle of a field and there's a giant white cane maypole. I wanted to create a space where that could exist.

When I’m planning a show or an installation, I conceptualize it as an experience, and I think about the choreography of the sculptures, and of my audience as well. I think about how the sculptures interact with each other in the space, and how the audience—their bodies—will move around them, like in a dance.

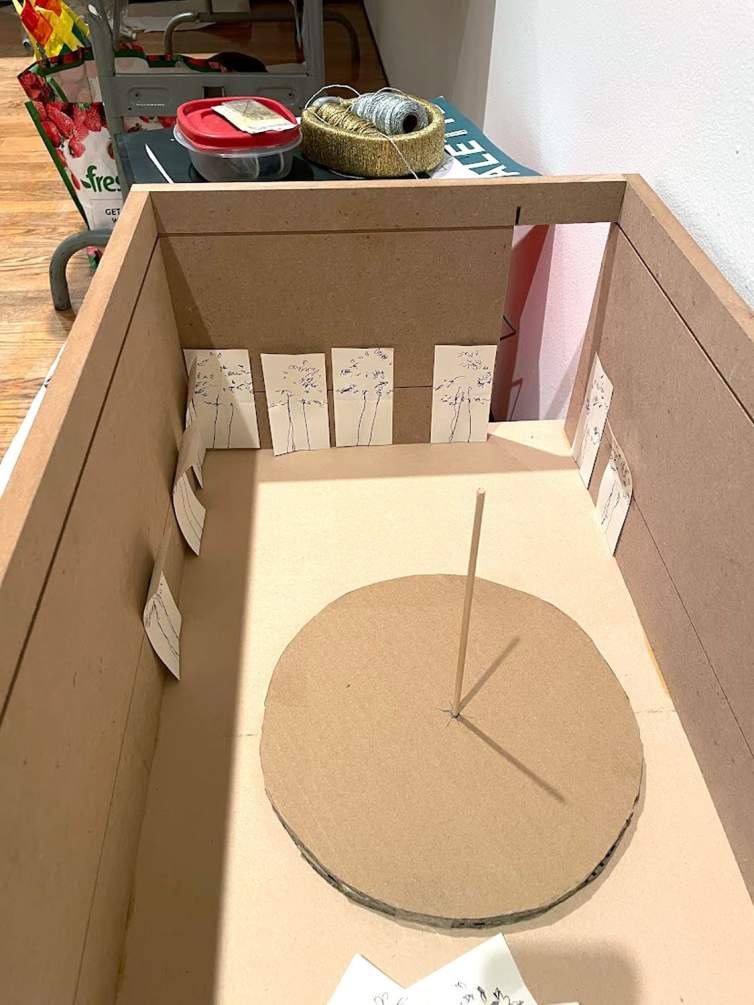

It was really helpful to collaborate with the staff at the Queens Museum. They made a scale model of the gallery space for me so that I could feel the space with my hands and map it all out, like where to place the circular pedestal and the trees.

With this particular installation, I gave each of the three Londons different gestures and body movements. This gallery space had two entrances, so I imagined people walking through one entrance. When they first entered the space, the first sculpture of London they meet is of her in mid-dance, with her head turned over her shoulder to look out at the viewers. I imagined my audience kind of being carried in and led through the space by that one London who is making eye contact with the viewers and inviting them to enter.

I wanted to capture that kind of mystifying experience when an animal makes eye contact with you, to be recognized or noticed by something that is other than you or something that you normally wouldn't be able to communicate with. There's something really powerful happening in that type of experience, and so I wanted the audience to be captivated by that one glance, and then come in and walk around the circular pedestal and follow the movements of the three dogs.

While they're walking deeper into the space, they come across the trees that I had installed on the walls—so I imagine the audience continuing to notice more and more details of the textures and the colors and the scale of everything. Moving further around the circular pedestal, they come upon my drawings and they make that connection, that these are the drawings that started it all and tie all the work together.

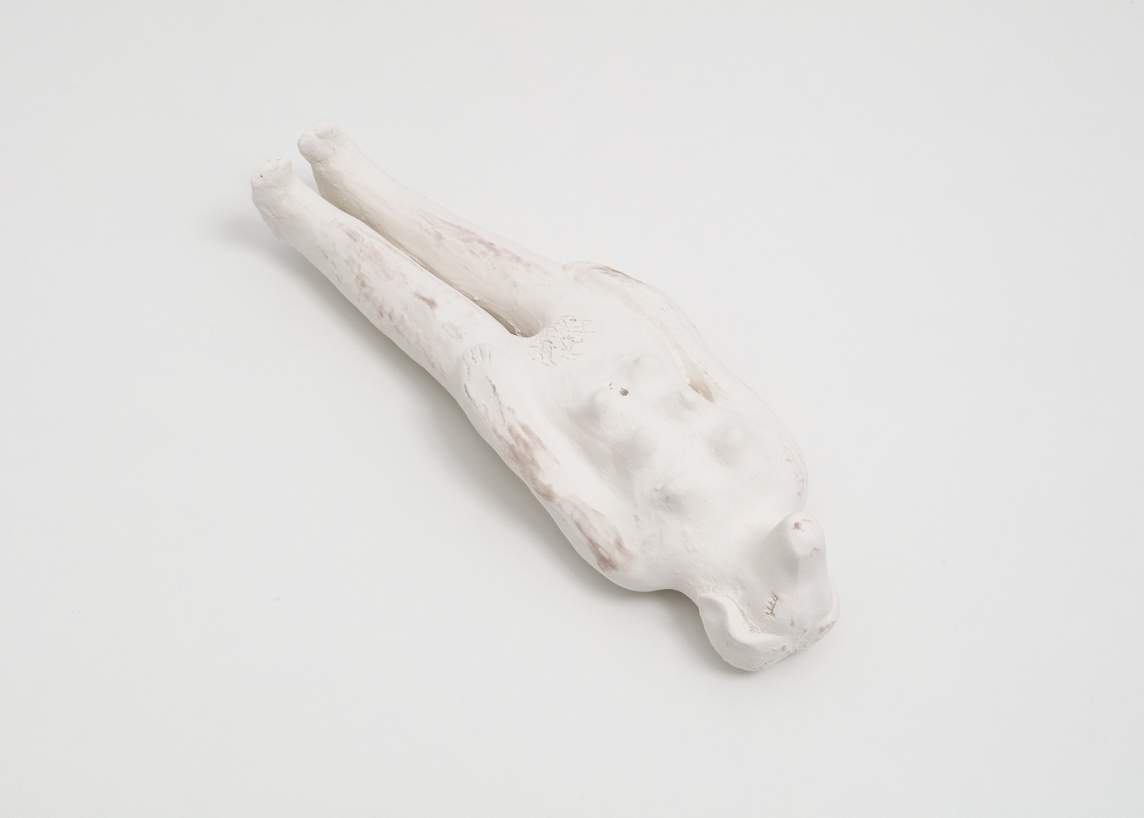

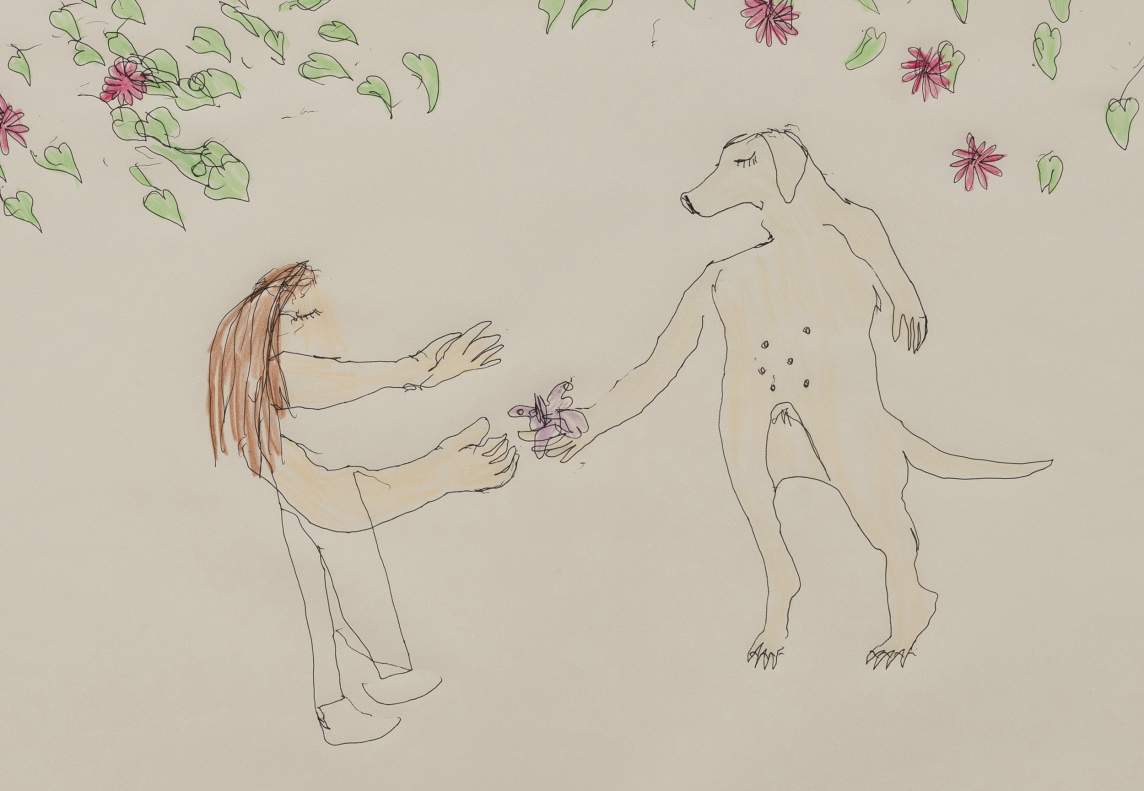

Some of my other recent work includes a character I created called Doggirl, which is a hybrid animal: me and my body hybridized with a dog's body—more specifically with London. It’s how I see myself and how I imagine the outside world sees me, as a girl who's dependent on a dog. But I feel like, with London and me, the way we are both dependent on each other really just makes us stronger together when we're whole or when we're working and collaborating together.

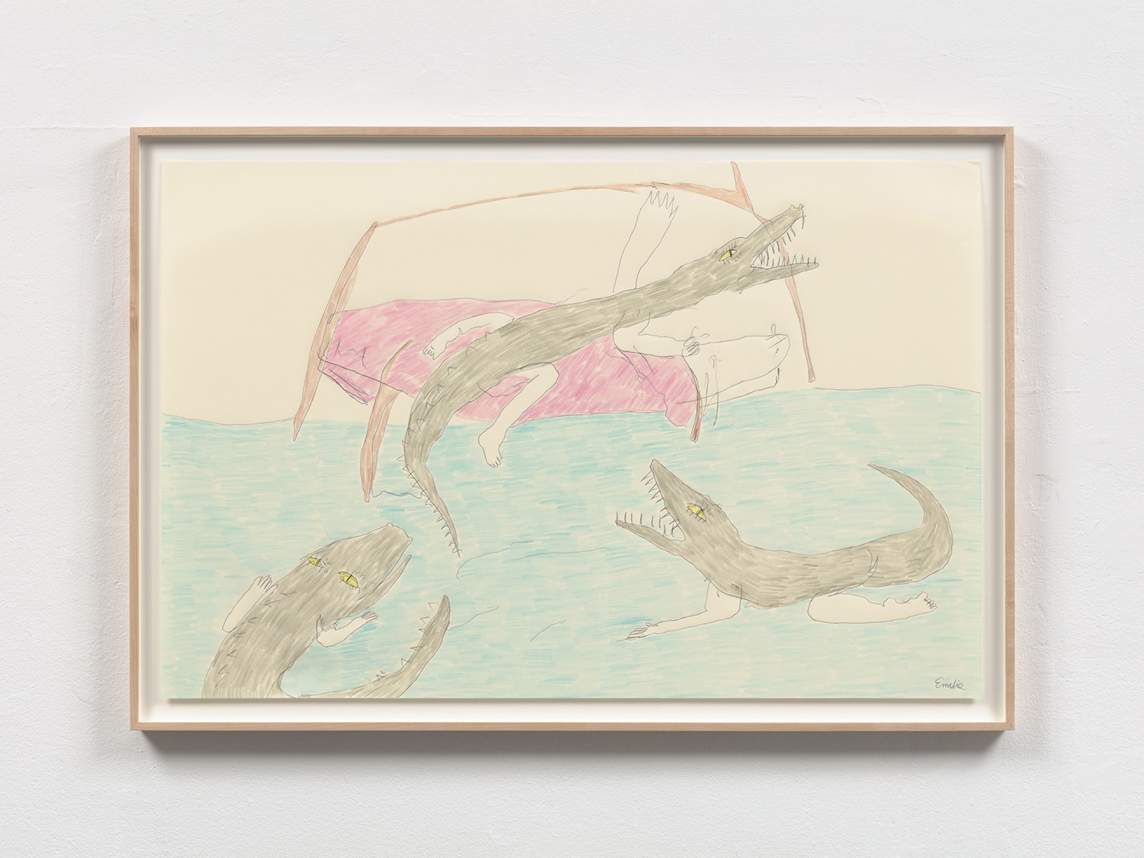

I also have another character, Alligatorgirl, which is an identity I like to play with that is more directly critical of the Anthropocene. This character grows out of my own identity, being native to New Orleans and from the South, and how alligators were always just another part of my life. Growing up across the street from a canal and near the Mississippi, I constantly saw alligators floating around, just hanging out. I didn’t really see them as a threat, even though they certainly are or were an apex predator.

I see myself now as being tied to the alligators and the threat of global warming, which is something that humans play a huge role in. Alligatorgirl was born after Hurricane Ida, which destroyed a lot of the area where I'm from in Southern Louisiana, and also affected people where I live now, in New York City. It felt really close to home, and I feel like this is just becoming a greater threat to all along the East Coast now.

I’m thinking about alligators and how their worlds are becoming closer to the human world, because their homes, the wetlands, are also threatened, and the wetlands serve as a natural barrier against hurricanes and flooding. It really is heartbreaking for me to read about cases where the wetlands, which are such a huge, important part of our natural environment, are deteriorating so quickly because of humans' expansion into them.

So I created Alligatorgirl as a direct response to the anthropocene and the patriarchy, and I see it as a feminist icon or a symbol for me, too, because I've read stories where men would do really stupid things with alligators—swimming in the water with them, trying to jump over them, getting up really close. And then they get eaten by an alligator, and part of me is like, well, you deserve that. What did you expect? And then it feels like there's also an injustice to that, where they take it out on the alligator.

I've been working from home for the past year and a half. I do a lot of drawings and I make a lot of my clay sculptures here. I have four studio tables set up, and I also really enjoy working in bed. My partner, Kirby, has been really helpful in carving out work space for me in this apartment that we share. As a disabled person, it's been really helpful for me to be able to work at any time that works for me. And it's also been great to be able to work from home because I can take care of London, who is kind of in hospice care right now. So it feels good to be able to spend this time with her and also to spend a lot of time in the studio.

Process-wise, my drawings and my clay sculptures go hand-in-hand, because with both I'm starting from nothing and I'm sort of problem-solving. With drawings, I have my tool, which is just a pen, and then I have my paper in front of me, and I have to decide, where do I make my first mark? It kind of evolves from there, and just keeps building up, as I’m working through how to make this image fit on a piece of paper.

When I’m sculpting with clay, it's also very much a built-up process, like at what point do I start with this body of clay in my hands? I also really enjoy painting my clay sculptures, because I trained originally as a painter, and I still have a really strong memory of color, how to mix colors, what kind of paint works best with the type of object that I'm creating. All my ceramics are painted either with oil paint or acrylic paint. I never use glazes.

Right now, I am preparing for my solo show at David Peter Francis Gallery in the Lower East Side of Manhattan, which will open on May 8th, so I've been making a lot of new big drawings and small ceramic sculptures. What I've been focusing on with this new body of work is the idea of the afterlife—death, and both the sadness and the joy of celebrating a life. I've been thinking a lot about this because London is nearing the end of her life, and I want to make sure that she has the best life and to really celebrate and honor the legacy she left for me. Being from New Orleans, the end of life has always been a celebration. I've seen a lot of parades with marching bands and a coffin that's decorated to celebrate that person's life and the beginning of the afterlife into a new world.

Imagery that's been coming up a lot for me recently is beds—thinking about beds as a very multipurpose place. For me, a bed is where a lot of the creative process happens. It's where I can dream, and a lot of my work is inspired by dreams and fantasies, and it's also a place where London and I cuddle together. This is where I draw, and it's a place where I rest. It's a place where I heal to regenerate. I’m thinking about the sick bed and about the deathbed.

Personally, I don't necessarily believe in any religion, but I do believe in a spirit world, and I think about dreams as a space where we can interact with or see spirits—where we can convene. I see London a lot in my dreams, and so I feel like this is a space where we'll be able to continue existing together in the afterlife.

A body of work that I recently created will show at CASTLE Gallery in Los Angeles, from March 29 - May 24. That work also focuses on London and her afterlife, thinking about other spiritual practices that are pre-Christian or pre-monotheism. The exhibition is called Votives, and I’m thinking about votive sculptures and how they are like a physical embodiment of that person who is being worshiped, kind of like an altar.

Other imagery that's been coming up in this new body of work is butterflies. I have some sculptural works in progress of London sprouting butterfly wings on her back. That body of work will also be included in my show at David Peter Francis Gallery. I’m thinking about the butterfly as this transformation or metamorphosis from the corporeal body into a more spiritual angel, heavenly body. I’m imagining an afterlife for her as a transformation—becoming something new rather than an ending.

Interview and editing by Jenny Gill. Learn more about Emilie Louise Gossiaux’s work at emiliegossiaux.com.