In the Studio: Samira Abbassy

“My attempt in depicting the human form is almost like a psychic x-ray, so the n...

Dawn Cerny is a Seattle-based artist and 2022 Joan Mitchell Fellow. We interviewed her about her work and creative practice in April 2023. The following is an edited transcript of that conversation.

In the studio, I ask myself, What can a singular expressive object do? How can I practice wrangling the sensations of what I know amidst the sludge of what I don’t know? Because I have a philosophical bias, the desire is to sit without knowing, which is not an easy thing to contain in an elevator pitch. And I know this because 24 hours ago I tried to explain my work to a man on a flight from Iceland to Seattle. That ended with a quite polite curiosity.

I should say that I am making work about how frustrating it is to make nut-free school lunches, but metaphysical and slapstick.

I'm really interested in what is at stake within a sculpture and how the surface can become a foil for what is happening underneath. I have a great suspicion about things that are tight and known, and I gravitate toward things that are uncomfortable, unfamiliar, and past language. I look for ways to almost have a recursive relationship to mediums as a means to enhance both my not knowing and my knowing at the same time. My friend Derek Franklin coined this “the virtue of mediocrity,” and I have stolen it and applied it to all parts of my life—from the way I use materials to dinner time.

At the same time, I admit to having a real thirst for a rigor within my own work, a rigor within the way that I read and think, a rigor within my intuition as well. And even though a lot of this language that I use is about unknowing, and I’m using the term “intuition” or using my life as a mother to shape the way that I'm thinking about obstructions or interruptions, I think the way that I come to those things is like the rigor of the aikido—using your circumstances to your benefit, even though it is clearly a disaster.

In this way, I think I'm working, at a slow pace, to build a representation for people who are living and working in between—meaning that they're not always in the studio, they have part-time jobs, they are caretakers in many different capacities, or they're grappling with a layered cake of catastrophes and working really hard to pay attention to those as the content. That is the thing that is at stake, within this work. I’m taking at least my time on this earth to build a representation of being a woman, being a mother, being a daughter, being a wife, being a friend, being an enemy. And building out an archetype that is larger than what we've known before—not just of what a woman could be but what a person can be.

I use a lot of materials that speak to the amateur trying to figure something out—materials that are relatively accessible, at a Michael's or a hardware store, which points to this urgency of figuring something out within the economy of the time and space and resources that I have, which is not a luxurious economy. And I have a lot of questions about how one uses materials or scale to shift the way that people perceive value and worth, related to something being permanent versus something being fragile, something deteriorating over time versus something that will be here when we're all gone.

There's a formal sleight of hand in my choice of color. I use a monochromatic surface within a lot of my sculptures because the forms are sometimes so fragile and flimsy that that color is this way of saying, "I'm in a uniform. It's okay. Take me seriously." I think about women with the foundation they use to cover their face up. It’s about keeping it together so that you can be perceived as serious.

This also dovetails into my first love, which is theater. Theater taught me how to be a person and taught me about empathy and listening and the voice and transformation. It showed me ways that something, through time and illusions and tricks—the set, the lights—can make people feel and can transform them or make them think.

I utilize the methods and tools of theater within my own sculpture practice, in that I don't think that a sculpture is just an icon. I work with the understanding that a sculpture can be a set or a prop, or the actor. I talk a lot about a set of actions or a taxonomy of gestures—a slouch, a point, a poke or dangle—and use this taxonomy of verbs and sensations within my sculptures. And then of course, in exhibitions, I'm very interested in the improvisational potential for new sets of verbs and sensations to develop between the works, the space, and the audience.

In 2017, I worked on a collaborative sculpture project at the Henry Art Gallery with the construction collective Kraft Duntz. My sculptures were in this large-scale project, but then in the midst of it, I took all the transcripts of all the texts and emails that we wrote while we were putting this exhibition together. This is when Trump had just been elected, and there were all the complications of putting on a museum exhibition and trying to French braid all of these different concerns and constraints. So I took the texts and ended up making those into a play that I then had some comedians perform in the museum as well. So again, there’s this recursive relationship with the formal concerns that I have as a sculptor, and then moving back and forth between the practicalities of how things get made or the context of something getting made or one's relationship with it.

I see the home as an inherently theatrical place as well. There’s Thanksgiving dinner and racist uncles and even my own fury at my family's shortcomings or not getting my way. It's like Chekhov—it's funny, it's sad, it's everything. And the home is the most ideal place to live with art because the scale is so much more in relation to your body and you're wanted there and you can live with it so much that you can also ignore it, which I also think is a really exciting prospect.

Within the theater of my own home—I live in a very small bungalow with my son and my husband—I started building specifically to the constraints of the Subaru Forester that I use to bring work around. So I use my home and the limitations of my studio, which only has a ceiling of seven feet tall because I'm in a basement, as a really perverse way of setting constraints that shape the scale of my work.

I’m really interested in the ways that the scale of a thing can move people to assume something about its use or value within their everyday lives. I make this joke about sculpture always being in between the cathedral and the coffee cup, as these two vastly different material and time mythologies. One is invisible and one brings you to your knees.

Many years ago, I was showing a large sculpture with these kinds of shelf-like levels. This was in the early days of Night Gallery in Los Angeles, and I remember that during the opening, people were putting their beers on my sculpture. I was kind of delighted by the idea of ambivalent collaboration. And I realize that this is quite a female thing, to be like, “My sculpture is serving you, it's in the way, but maybe I can hold your keys.” But I was charmed by how the furniture-like scale of a thing could invite people to use these places, these surfaces, to put things on and then the sculpture would, in return, use the poetics of stuff and aimless gesture as part of the sculpture. There are hooks and vessels and shelves and holes and clips that imply an invitation to hold or display.

The scale of my work has shifted over the past few years. When I got breast cancer, in 2021, I had to respect the reality of having different physical limitations. In my sculptor mind, it meant, "Okay, well, I guess I'm just going to have to move to tabletop work,” because it was the scale that I could physically execute. I'm a big believer in the value of subjective experience in forming a work, and using the conditions of my own daily life to make a meaningful, if arbitrary, shift. There is something really poignant, if for no one else than just for myself, about really accepting those conditions and moving forward.

So I started making these tabletop sculptures while I was in treatment. And I really like this idea of the tabletop sculpture being really the only sculpture that most people could afford to actually physically put in their homes. There's a way that smaller scale or tabletop scale sculpture can be a proposition for looking and experiencing what a sculpture can do in a space with ambient light over the time of day, interacting within the home.

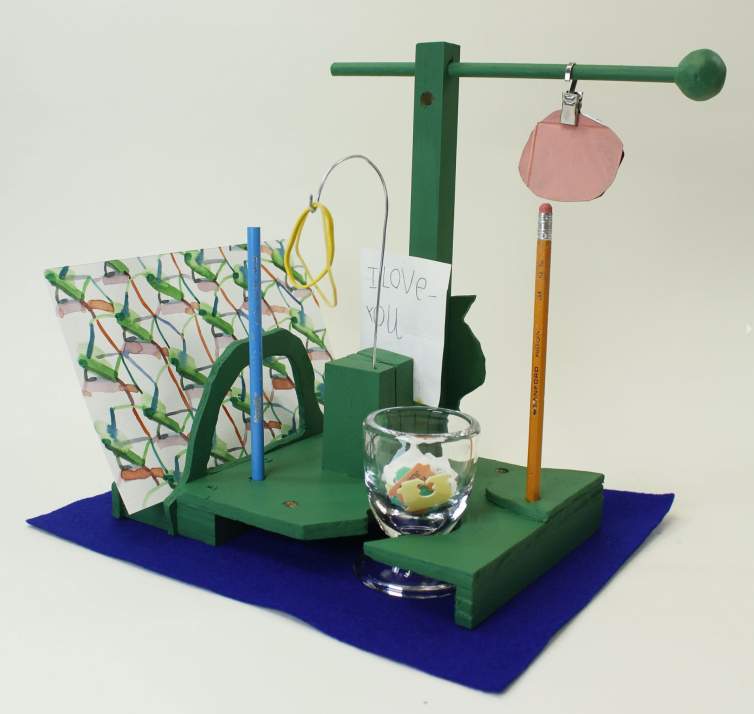

Over the last year or so, I've been working with Robin Wright of RITE EDITIONS in San Francisco to produce a unique edition of tabletop sculptures that are modular. It consists of a glass egg cup that I worked with a glass artist to make based on this prototype that I had designed a couple years ago at Pilchuck, an experimental glass school started here in the Pacific Northwest by Dale Chihuly. So it has this egg cup, and then I built a sculpture made of wood that the egg cup sits within. So it is a stage, and then the stage is inhabited by the cup. Then from there, I designed this sculpture with parts so that people could construct it in the way that suited their lifestyles. So it comes with these wooden pegs and these wire hooks and these clips, and there are slots. There's all these invitations for sticking pens in it or pieces of paper or parking tickets or photos of nieces. And it also has these different color textiles that the thing can sit on. So 12 of these boxed sculptures were sent to curators, friends, or people I admired—poets, philosophers, artists, writers—who all consented to receiving a sculpture. It was a gift that they were invited to live with.

Over the next six months, their job was to photograph the table-top sculpture and send me photographs. And then at the end of the six months, write some sort of text. It could be anything—a fictional story, or a list, or it could even just be like, “I never had time to take this out of the box. I didn't deal, my life was in chaos.” So the idea was to use these subjective experiences with this gifted sculpture as an invitation for improvisation and collaboration, which can be very uncomfortable as well. We're currently making a book out of that material collected from the participants. A limited number of the sculptures are for sale at a ridiculously reasonable price. Because they're tabletop sculptures, people don't know what to do with them. So I'm now making infomercials videos, to show what is in, and how it works.

As my body has been rehabilitating, working on small scale sculptures has been prudent but this spring I am slowly working large in my backyard. After years of working so diligently within the scale and economy of my domestic landscape, I started wondering what would happen to my work if I translated the transitory domestic into something large and public and built to last. Can a public sculpture do that “yes, and” thing they teach in improv class? Am I talking about a playground? I will let you know what I find out.

Interview and editing by Jenny Gill. Learn more about Dawn Cerny’s work here.