Joan Mitchell Centennial Symposium at Art Institute of Chicago

From October 23-24, 2025, the Art Institute of Chicago, in collaboration with th...

When I was first introduced to Joan Mitchell’s paintings by my high school art teacher, I remember being struck by her bold mark-making and vibrant use of colour. Twelve years later, these are still aspects of Mitchell's work I find compelling.

As an undergraduate at the University of Cambridge, I became fascinated by the women associated with Abstract Expressionism. I later did an MA at the Courtauld Institute of Art, which included a research trip to New York. I spent hours sitting in front of Mitchell’s Hemlock at the Whitney and Ladybug at MoMA. I knew then that Mitchell was an artist I wanted to do sustained research on in the future. I wrote my MA thesis on the relationship between control and order in Mitchell’s work and this was the starting point for my PhD.

Mitchell, alongside Helen Frankenthaler and Alma Thomas, is one of the case study artists in my PhD. My research addresses intersections of gender, materiality, and abstraction, developing a theory of doubt or indeterminacy. To do this, I synthesise the study of art works and process with sustained archival research.

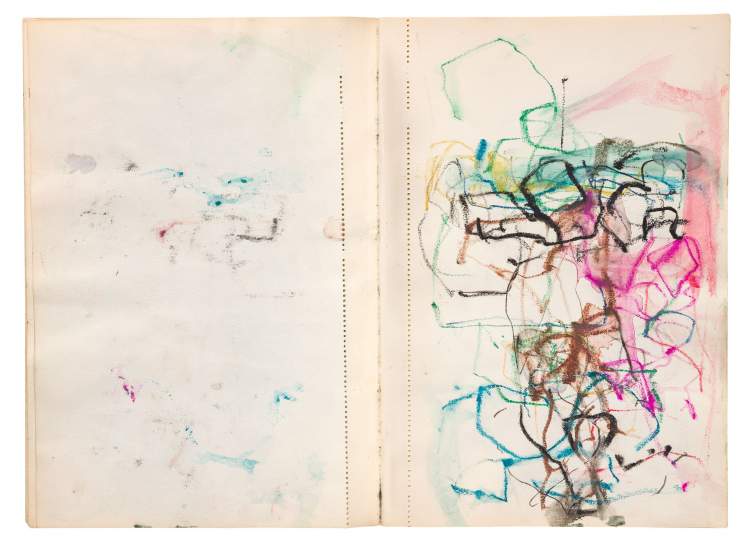

My dissertation chapter on Mitchell focuses on her approach to challenging painting from within. I frame this as an internal reckoning with painting’s traditions. I find it striking that Mitchell both consistently identified with Abstract Expressionism while seemingly testing the style's limits. I pay particular attention to Mitchell’s process, including her commitment to oil paint, varied approach to mark-making, and more broadly how her mode of working was affected by her different studios. While I focus on Mitchell’s painting, I investigate the significance of drawing within her practice through studying Mitchell’s pastels and sketchbooks. I am also interested in Mitchell’s contradictory relationship with feminism and the ways she negotiated her position as a woman artist.

I recently presented a paper in the “Joan Mitchell and Second Wave Feminism” round table conversation at AWARE in Paris. A brief excerpt follows:

“Mitchell can be seen as using irony as a subversive feminist device within her paintings. In an interview with critic Douglas Davis, Mitchell quipped: ‘There are four kinds of art, pop art, op art, slop art, and flop art. I fall into the last two categories.’

“Mitchell’s categories constitute a humorous dismissal of contemporaneous approaches to abstraction.

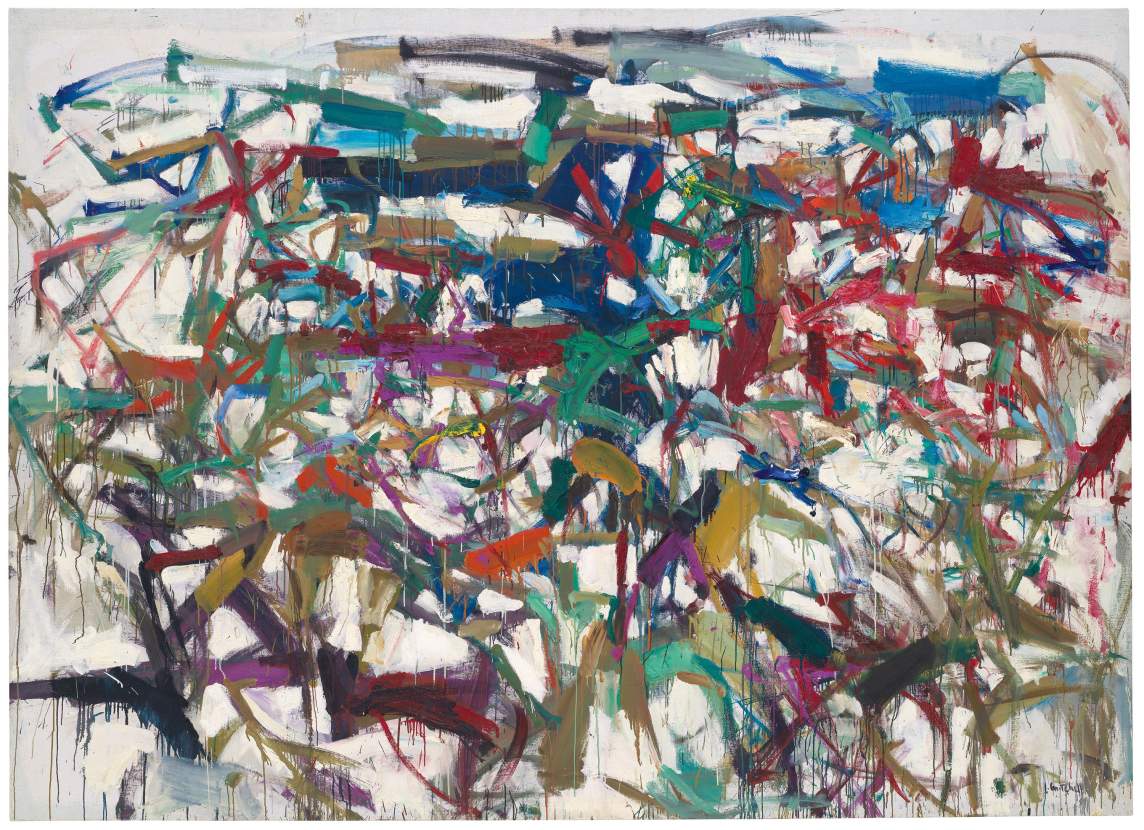

“In She Changes by Intrigue: Irony, Feminism and Femininity, theorist Lydia Rainford asserts irony has long been used as an agentic, feminist device to question established ideas and negate a structure’s values from within. Mitchell’s painting Swamp (1956) illuminates her agentic use of irony. The title parodies the formal language she knowingly adopted within the painting. Intriguingly, Mitchell persistently rejected ideas of accident within her work. For example, in an interview with Irving Sandler she stressed, ‘If I saw an accident I would use it…. And then it’s no accident.’ Ostensibly Swamp appears muddled and ‘mistaken,’ as if multiple ‘accidents’ have taken place, submerging the painting’s surface. The murky peach, blue, black, orange, and red strokes at the centre of the composition are almost reminiscent of paint squeezed straight from the tube. On the lower register, the broad-brushed sections of white, brown, and grey echo the swamping of pigments within Mitchell’s paint palettes

“However, on closer looking, Swamp demonstrates Mitchell’s use of a structured centripetal composition. The painting is further defined on the left where Mitchell uses an “X” motif, and on the lower right where light brown brushstrokes divide passages of white into modules. Belying the painting’s ostensibly swamped surface is a careful process of ‘seeing’ and ‘using’ mark-making. Viewed through Rainford’s theory, Mitchell’s identification with ‘slop’ and ‘flop’ formed an ironic feminist negation of the use of these terms in framing her work and the value of spontaneous heroic mark-making in Abstract Expressionism.”

My work on Mitchell is underpinned by archival research. I feel very fortunate to have been awarded research grants from the Terra Foundation for American Art, University College London, and the Getty, which have enabled me to undertake extensive work at archives including the Joan Mitchell Foundation, the Getty Library Special Collection, and the Archives of American Art.

Through archival study, I aim to recentre Mitchell’s voice while considering where it is possible to push against her interpretations. I draw on primary materials including photographs, newspaper clippings, letters, and interview transcripts. I think it is particularly important to turn to the archive when studying women artists as so frequently their agency is diminished through limiting biographical accounts or in the construction of a male-dominated art history. Mitchell rarely made big claims—be it about painting, politics or people. Often what Mitchell didn’t say tells you as much as what she did.

Mitchell will be central to my future work. I finish my PhD early next year and plan to turn my dissertation into a book. I am also developing a new project on women of the American Print Renaissance. I am excited to research Mitchell’s overlooked—yet extremely interesting—lithographs and etchings as part of this project.

Something I think isn’t written about enough—and I would love to do more work on in the future—is how funny Mitchell was! Reading her correspondence and interviews illuminates Mitchell’s wry sense of humour; to me, this characteristic also manifests in Mitchell’s paintings.

Cora Chalaby is a PhD candidate in History of Art at University College London. Learn more about her work here and on Instagram: @corachalaby. Interview and editing by Jenny Gill.