Joan Mitchell Centennial Symposium at Art Institute of Chicago

From October 23-24, 2025, the Art Institute of Chicago, in collaboration with th...

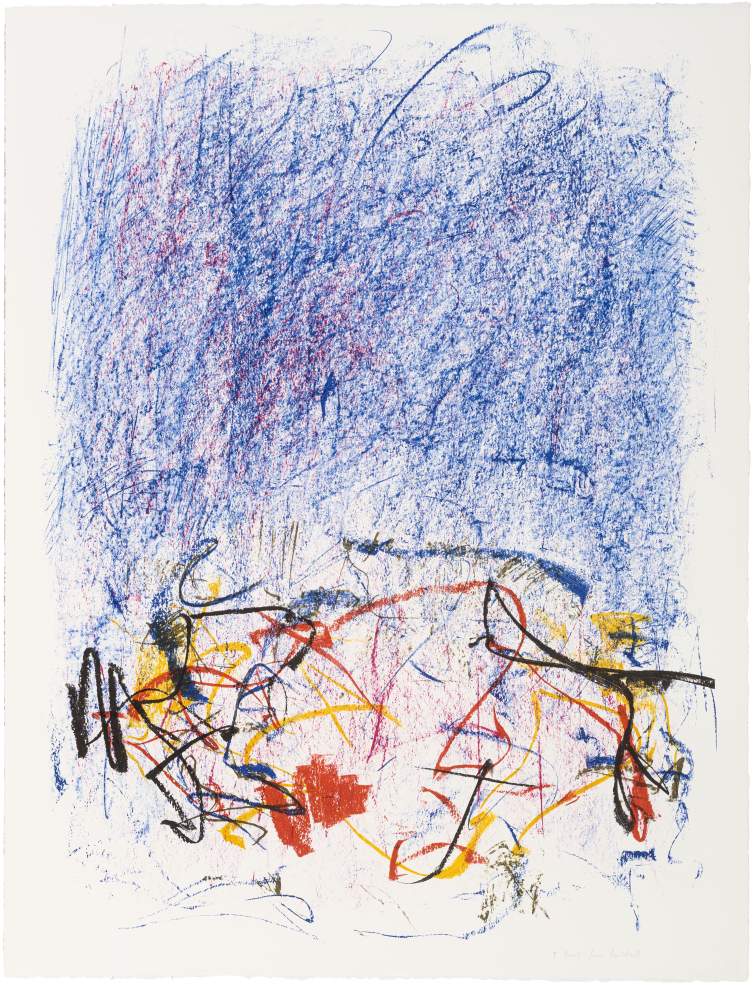

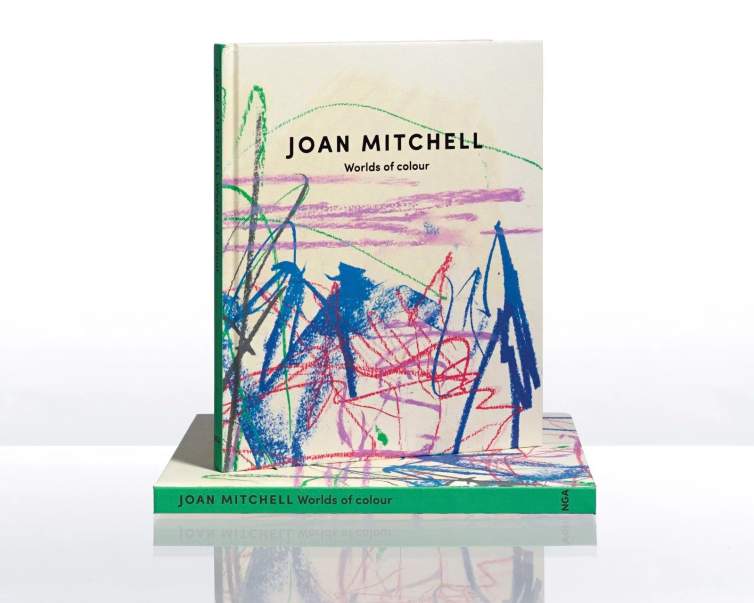

I was first introduced to Joan Mitchell’s work in my former role as Assistant Curator for the Kenneth E Tyler Collection at the National Gallery of Australia. There, I was presented with the (previously) rare opportunity to develop a monographic exhibition on a female artist from the collection. At that time, I knew very little about Mitchell and her career, although a few months prior I had encountered the lithograph Joan Mitchell, Bedford I (1981) in storage and been struck by the work. I immediately decided that she would be the artist of focus. The exhibition would become Joan Mitchell: Worlds of colour (2021).

Drawing from the Kennth E Tyler Collection and Archive, and focusing on Mitchell’s printmaking, the exhibition formed an initial component of the now iconic Know My Name initiative at the National Gallery of Australia—a series of exhibitions, commissions, education programs, and events that celebrate women artists throughout history and in the contemporary.

In developing the exhibition and the associated publication, I was continuously dumbfounded by the lack of published material on Mitchell’s works of art; this sparked my deep engagement in her artistic practice. I am endlessly curious about how complex her paintings are, how complicated she was as a person, and how slippery it is to carve out a neatly defined place for Joan Mitchell in the ‘canon’ of art history. Sarah Roberts and Katy Siegel’s publication “Joan Mitchell,” also from 2021, is a remarkable contribution to support this effort.

I’m continuing to work on Mitchell as the focus for my doctoral research, which centers on Mitchell’s lifelong engagement in poetry, specifically the lyric or lyrical tradition in the arts. As an Australian curator and researcher, the post-war period of North American art dramatically shifted our cultural landscape—Jackson Pollock is a household name. The task I set myself was to objectively understand why Joan Mitchell isn’t. I don’t want to give too much away, but I respect and cherish the material by other authors who have also contributed to this space, such as Eileen Myles, Maggie Nelson, Jenni Quilter, and Richard Shiff—all of whom navigate a deeper understanding of the space between objectivity and subjectivity.

Archives have been crucial for my work, and my research approach is to be led by them. I was so fortunate to spend a fortnight trawling through Joan Mitchell’s personal correspondence in the Foundation’s collections. I went in without any research angle or argument in mind. I wanted Joan Mitchell, her friends, and her family to guide my historical and theoretical approach to defining her context between poetry and painting during the New York School and thereafter. I return to her letters when I feel lost. Mitchell’s mother, Marion Strobel, is a key touchstone that I draw on—I read literature and poetry they reference. Also, the pithy commentary from Frank O’Hara about the highs and lows of their ‘scene’.

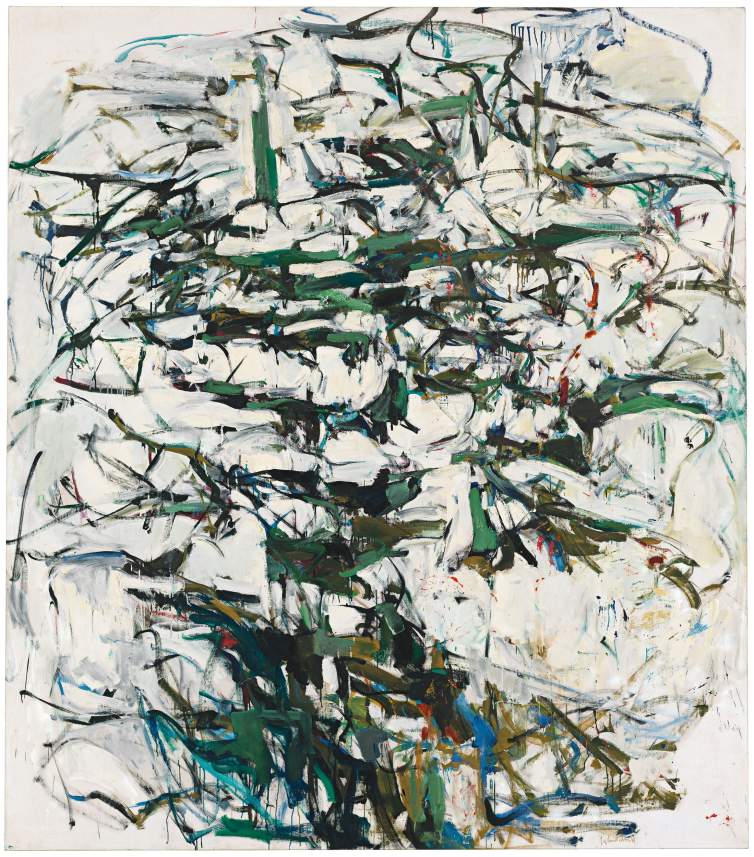

In-person examinations of paintings have also been critical to my research. I had the remarkable opportunity to view many works in storage last year in various public collections in the United States. In particular, Hemlock (1956) took my breath away. I had to apologise to the registrar at the Whitney because I gasped and said, “Wow, f*ck, now THAT is a great painting.”

For anyone who is interested to know more about Mitchell’s printmaking specifically, you can certainly refer to Anja Loughhead (ed.), Joan Mitchell: Worlds of Colour, National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, 2021. A brief excerpt:

“Each work presents her meditation on mortality, the culmination of various days, months and seasons of life. Considering all of her ‘remembered landscapes,’ the recurring portrayal of trees distinctly carries her ‘remembered feelings’ on the subject of life and death. Mitchell’s personal iconography commemorates the cyclical nature of beginnings and endings: through an outpouring of sorrow and anger, she transformed these sensations into a reverence for life. This system of spiritual catharsis is evident in Flower III and within Sides of a river II: both motifs—flowers and water—are interconnected with seasonal change. Mitchell’s work is haunted by her own presence as it endures the passage of time.” [Anja Loughhead, p.26]

Additionally, for any technical printmaking fanatics out there, I highly recommend the recently released publication Jane Kinsman (ed.), Tyler Graphics: Catalogue Raisonné, 1986-2001 (National Gallery of Australia, Kamberri/Canberra, 2025), which has been a massive undertaking by my peers and includes Joan Mitchell’s collaborations with the Tyler Graphics workshop during this period.

Anja Loughhead is a PhD candidate at Monash University and currently Project Manager, Capital Works Project at the National Gallery of Australia. Learn more about her work at @anja_loughhead. Interview and editing by Jenny Gill.