PART 3: Beginning Steps for Planning a Retrospective

Planning for a retrospective is no easy task. But the end result is very rewarding—for the Artist and all those involved in the preparations.

Mel Chin’s retrospective, opening February 2014 at the New Orleans Museum of Art, has been my main focus for the past few years as I work to develop a comprehensive and usable archive through the CALL program.

The overall planning of the retrospective takes the support and effort of numerous people. The collective effort to sort, organize and inventory the artwork now serves as the central location for research and information on Mel Chin’s life’s work. In this entry my intention is to present the infrastructure my team and I developed for preparing for the retrospective. These areas of focus may help you build a framework for preparing for a big exhibit and/or catalog.

Creating an Inventory

First, review Part 1 for pointers on going through the cataloging process of artwork. In making the inventory, try to keep these ideas in mind:

Where are these pieces located? Are the pieces inside crates? Do crates need to be built? When was the last time the piece was inspected? Is this piece ready for exhibition as it is?

While you are creating an inventory, make note of what pieces need to be reviewed, in case there is some damage or repair needed, or perhaps the piece needs a new frame.

Find out where other pieces are, via collectors or museums or galleries. Try to get in touch with the people or institutions to determine what condition the pieces are in, and if the pieces are stored in a shipping crate.

For example, Mel’s work is stored in several buildings on his property, as well as in various institutions’ collections around the globe. At any given time, his work is also on exhibition in various locations.

I designated a period of time to locating these pieces, making a notation on their condition and whether or not the piece was ready to be exhibited. Many of Mel’s work needed some extra care before being shown, particularly the installation items that have electronic components.

Assess what needs restoration and what is ready to be displayed

After creating a solid inventory, then be realistic about what pieces are ready for exhibition in there current state.

If there is restoration needed, create a list of what needs to be done. Does the work need extra professional input (like a paper conservator)?

It was really helpful to me to create a list outlining each piece with the specifics around what needs to be done. I’ve worked closely with Mel to determine these factors, since many of his works are installations and have several components. We worked on the biggest details, like replacing an integral part, to the smallest details, such as making sure the plexiglass isn’t scratched.

Create a Checklist for exhibition with Curator

This may seem obvious, but the checklist is key for keeping your work focused and clear, as day-to-day activities can pile up. With an exhibition checklist you will be able to focus your attention on what pieces, within the checklist, needs extra attention.

For example, Miranda Lash, curator of Contemporary Art in New Orleans, has had one main checklist for Mel’s exhibition. Some pieces shifted in and out of the list due to logistics, planning, etc. But for the most part, the list has remained the same.

Also, the exhibition checklist has given me clear parameters to focus on getting specific information prepared for the exhibition and catalog research.

Find research/information about pieces

Most major exhibitions also have a catalog as part of the exhibit. Gathering research materials together has been a major focus for me to assist NOMA’s curator Miranda Lash in her writing and for building a comprehensive timeline in the catalog. It was also my strategy for locating the right images for the corresponding retrospective publication.

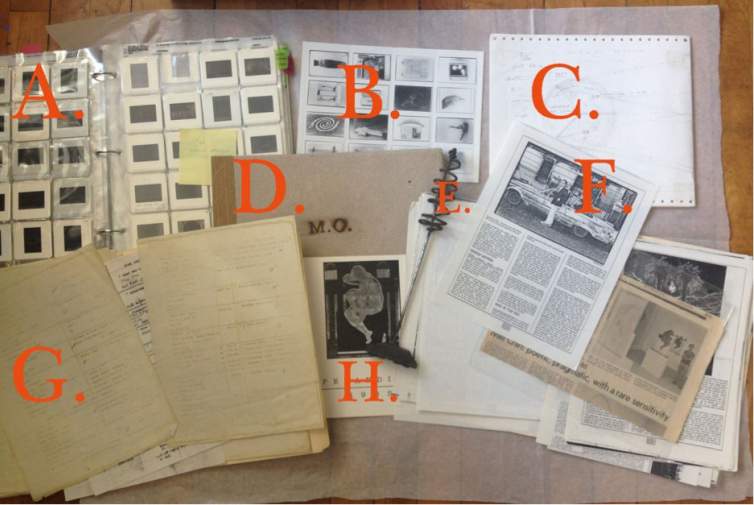

As I found information, I scanned articles, catalogs, and writings that corresponded to Mel’s pieces that were intended to be part of the exhibit. I then sent these items electronically to Miranda Lash. I often would find text and images that were obscure and rare to the public eye. Being able to locate and organize my research was essential to what and how I shared the information to be used for the retrospective.

Set a realistic timeline

I’m saving this for last, but it is a significant part of the planning process.

All of these activities take time and energy. More often than not, time for each task is underestimated due to it being a new task. Here are some helpful questions to ask:

- How long will the preparations of each piece last?

- If crates need to be built, how long will that take? How many people are needed to build each crate?

- How long will the research take for the catalog?

- How long will gathering the images together take?

- How long will the installations of each piece last?

For Mel’s show, it has taken around 3 years to get the research in order and locate the artwork to be; crated, prepared, tested, and ready for the exhibit.

These are some very important first steps for planning a large exhibition, like a retrospective. I think the most important element of preparing for an exhibition of this scale is to have clear communication and assignment of duties in the studio to the studio workers. This ensures that everyone stays on task and within the perimeters of a set timeline. As the artist’s, Archive Specialist, you can see the big picture for everyone to work toward and become the go-to person as detailed information is needed for each piece.