In the Studio: Samira Abbassy

“My attempt in depicting the human form is almost like a psychic x-ray, so the n...

Michael Meads is an artist based in Abiquiu, NM, who was in residence at the Joan Mitchell Center in Spring 2019. The following is an edited transcription of a conversation about his life and work, conducted in his studio during his residency, accompanied by photos from his studio.

I was born in Northeast Alabama in 1966 in a small town called Anniston, located at the lower end of the Appalachians not far from the Georgia-Alabama line. There was a big military base there when I was growing up, so you had a lot of diversity coming through Anniston. I was raised as a hellfire and brimstone Southern Baptist, but I managed to survive that.

I started making drawings when I was a little boy, not even walking yet. My mom had me sitting on the floor in the kitchen with crayons and paper, and I’d just sit there and make marks and it kind of started with that. It kept me busy enough, out of the way. I would doodle, and then over time, the doodles became more specific. When I was about five, I started watching horror movies on the TV. I loved the classic horror films and so I would start drawing the werewolf and Dracula and Frankenstein and then anything with Vincent Price. I didn’t really understand who he was, but it’s like, “This guy—this is my guy.” Also at a very young age, Halloween became very important to me. I remember it was my sixth birthday and my parents got me a Roman Centurion costume for Halloween as I was obsessed with Roman history, and I had the full costume—helmet, shield, breastplate, sword, the whole bit. I still have photographs of it.

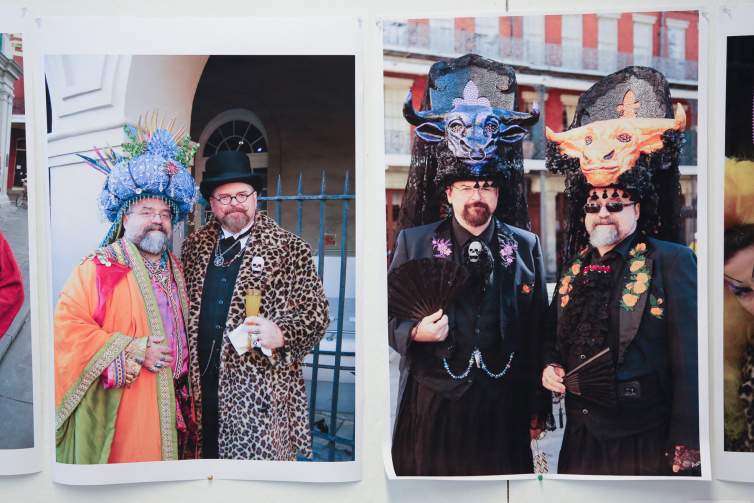

So, costuming and masking have always been really central to my life and work. I had to learn at a very early age to wear a mask. Where I was growing up, being queer was not the best thing to be, in fact it could be quite dangerous. And the smartest thing to do back then was to try to blend in.

In 1994, I met my partner, Charles Canada, who would become my husband. We made our first trip to New Orleans together for Halloween in 1996 and then moved there in 1998. The first house that we looked at to rent was a side-hall shotgun, a block off St. Charles near Washington Avenue. The realtor said, “I don’t want to scare you off, but you know the parades come down St. Charles, right there.” We were like, “Really?!!!” So we didn’t even look at another house.

In 2005, we moved to a place on Bellaire Drive in Lakeview that had a main floor and a loft, which is not the smartest decision we ever made. After Hurricane Katrina, if it was downstairs, it didn’t make it, and it was up in the loft, it did.

At that time, I was working on a show. I had a bunch of new work that was ready to go, and I hadn’t even photographed it yet—it was still in the flat files. It was a Friday night, and we knew there was a storm that had moved into the Gulf. I hadn’t been paying that much attention to it because you get into that kind of lazy way of thinking about hurricanes, you know, it will miss us as it always does. And so we had planned to have some friends over for a small dinner party. It was NOT a hurricane party, which I think is in bad taste. We had the news on, watching Margaret Orr, the local weather person, and she was becoming more and more concerned. It was getting late, and I decided to go ahead and crash for the night, and Charles stayed up with our guests a little longer. The next morning I got up and walked into the bathroom, and taped to the lid of the toilet was a note from him that said, “Wake me up when you get up. Category 4 heading right for us. We need to decide what we’re going to do.” I still have the note. It’s framed.

So that morning, we turned on the television and Margaret Orr—she never gets rattled, she’s like this total professional, and we’re watching her come unglued because by the morning, it had become a Category 5, and it was starting to bull’s-eye New Orleans. Then the mayor decided it was time for everyone to think about heading out, and we always evacuate because we stayed one time (Hurricane Georges) and that was a bad decision. So we packed up for what we were thinking would be a long weekend. We figured the power would be out in New Orleans, which means no AC, we’ll just stay at my sister’s in Anniston. We’d have a barbecue, have some friends over, hang out for a few days then go home once the power was back on. Charles was paying attention to what’s going on, we had satellite pictures, and everything seemed fine, like, “OK, there’s a couple of trees down in the backyard. It looks like there are some windows blown out and the air-conditioning unit has been blown off the roof.” We’re like, “Whew.” And then things started to take a turn, and the reports started coming in. We went back to the satellite images and saw that part of the 17th Street Canal levee had collapsed on the Lakeview side—our side—just a few blocks from our home. And so suddenly, what was supposed to be a long weekend at my sister’s... I think we were able to come back six weeks later to salvage what we could. Then we went back to Alabama, where we were exiled for almost two years.

Because my studio was in the downstairs of our house, I lost almost all of my work. At the time of the storm, I was preparing for an exhibition, all works on paper. By the time we got back to Lakeview, all of it was just pulp. You could see where the flat files came apart, and where the paper had settled as the water moved out.

We realized very quickly that we were going to be there in Alabama for a while. Charles is the techno part of the operation, so he started looking for emergency grants, because we knew our insurance company was going to screw us over, and FEMA, of course, was a nightmare for everyone. He ran across the Joan Mitchell Foundation Emergency Grant, and we got the paperwork filled out, got all the images together, resume, and all that sent in. We were afraid, we had nothing. I didn’t have a job to go back to, and Charles was trying to maintain his job in New Orleans remotely.

So I applied for and received the Joan Mitchell Foundation Emergency Grant. The grant money went strictly to survival—paying rent, buying groceries, etc. Not long after the grant, the Foundation contacted me and said, “Would you be interested in spending three months in an artist’s residency in Santa Fe?” They had an agreement with the Santa Fe Art Institute to use them as a residency. Much like the grant, it was a godsend because I needed some time to get my head together and Charles needed some time to get his head together and so I went out there for three months. Most of the artists at the residency during that period of time, this would be 2006, had all received the emergency grant and residency because of conditions after Katrina.

The majority of them were from New Orleans and the forgotten Mississippi Coast. The residency in Santa Fe was incredible. Charles came out for a week while I was there, and we basically drove all over New Mexico and just fell in love with it. Northern New Mexico has got to be one of the most beautiful places I’ve ever been, and we both decided that it would be nice to live there one day.

In 2007, we moved back to New Orleans and spent two years there, and everything was going pretty well. I mean, we were bat-shit crazy, but we were functioning. Then Gustav rolled ashore, and we had to do another emergency evacuation. We went to my sister’s, again, and we both kind of had nervous breakdowns after that. It was like, “We can’t do this anymore.” We’ve just spent the past few years trying to rebuild our lives and our world, and our friends have been doing the same thing. So we decided that as soon as we were able, we would relocate to higher and drier land, to New Mexico.

It was exactly what we needed. We found a therapist that deals with PTSD, and she really helped. I kept begging her, “Just move your practice to New Orleans! You won’t have a moment where you’re not needed.” I have some very dear friends that have still not gotten any help. I think everybody kind of lost a decade of their life. All of my friends, other artists that I know out of New Orleans, our careers should all be 10 years further down the road. And honestly, not just the artists but everyone. I think everyone’s life got so derailed that we’re only really now getting back to what we’re supposed to be doing or would be doing. You’ve had this 10-year-plus interruption, and it’s very problematic and tragic.

I consider New Orleans my hometown. Twenty-plus years, it’s home. For right now, I’m temporarily living somewhere else until I can figure out a way to come and go and have a little place here in New Orleans with absolutely nothing in it that I can’t live without. In the desert, I have my library, and I have access to the internet, and research that I do in preparation for my work. But at a certain point, no matter what, the well starts to dry up. Your creativity starts running low. The battery starts to run out of juice. So I applied for the residency here at the Joan Mitchell Center. I think I applied two times, and the second try, I got it.

Since I’ve been here at the Center, I’ve been doing a lot of reference photography, filling the well back up with visual information that I can use when I get back to the desert, like the architecture, street scenes. Especially if it’s raining at night, I get down to the Quarter and try to do as much photography of the wet streets and the neon lights as possible.

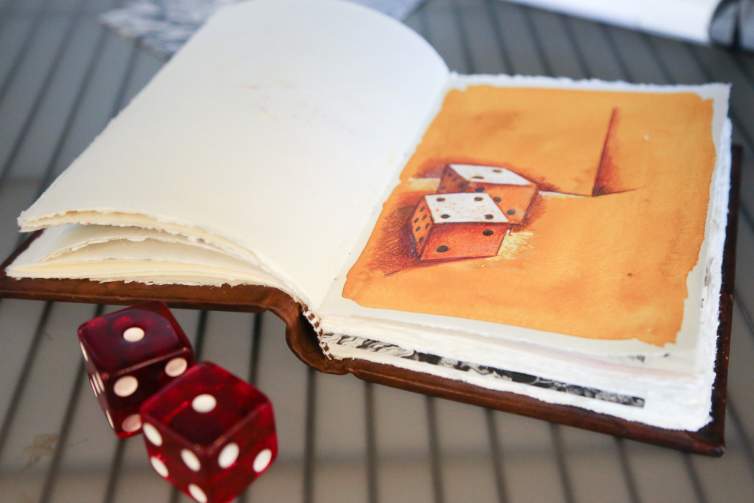

My work has always been based on lived experience. I grew up with story-tellers. I’m very much part of the Southern tradition of the storyteller. My grandparents, my great-grandparents were all storytellers. In storytelling, there’s mostly truth, but also, there is that degree of exaggeration—no good storyteller tells a story the same way each time. My great-grandfather would say the whole point of getting older is that you have great stories to tell. My work is always about what has been my world, whether it’s growing up in Alabama or being in New Orleans. I’ve kept a photographic journal since high school, and some of that survives still. When I make artwork, everything that’s going to be in the piece is something I have seen, and most of the time, I can prove it with a photograph. The event itself may be something magical, but everything in it was something I’ve seen on the street. I may be condensing some events, but everything is based in a lived reality. It's visual storytelling.

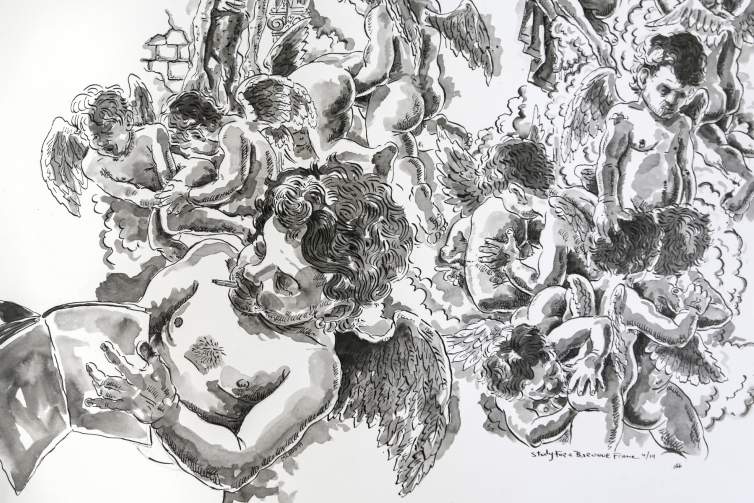

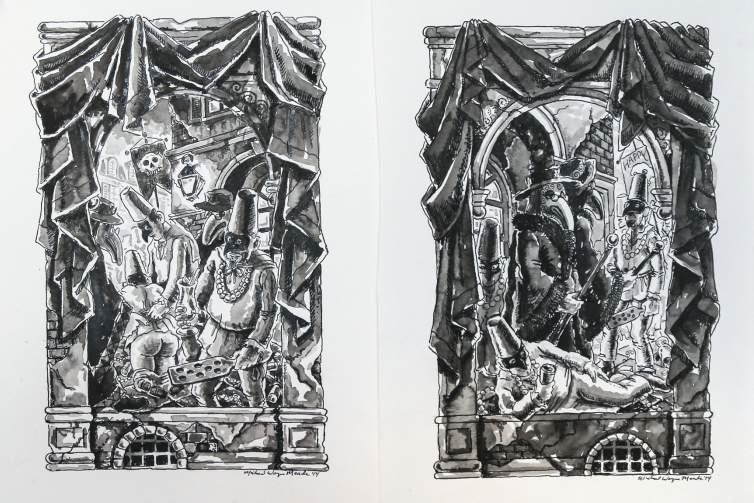

I’m obsessed with Wagnerian opera, and many of my drawings will be surrounded with a stage proscenium, often shown collapsing. The whole idea is that you’re looking onto the stage inside a huge opera house and everything happening there is the big finale of the last act of the opera. It ties back into the artifice of costuming, masking, performance, and storytelling. A dear friend said, “You’re just in love with the swag and the drag of the church.” Which is true. My world is the Baroque—I’ve never seen anything that I said, “Oh, that’s just too much.” More is more, and more is better, dot the dot, gild the lily, and then gild it again. Layer upon layer. I love how over the top it all is.

When we first moved to New Orleans, my work shifted into the world of Carnival, and mask making. And that is my New Orleans. People ask me how has the desert influenced your work, and I say, “Not at all.” The only thing is I’ve got a big wall in my studio where I can do really big drawings. The desert landscape is for contemplation and for healing, but the work is still about New Orleans.

Here at the Joan Mitchell Center, I've been trying to find a balance between being in the studio, trying to get some work done, and also wanting to be out and about in New Orleans, documenting things or hanging out with friends and reconnecting. Before Katrina, I had started a series of paintings of my versions of the Stations of the Cross, and they were all going to be set in the French Quarter. Everybody in them was going to be people that I knew from the French Quarter, characters that I’ve known for years, friends, settings, events. The first time Charles and I came to New Orleans, we were sitting in the window of Pat O’Brien’s, and this young man was coming down Bourbon Street wearing a loincloth and a bandanna, a big peace medallion, and he was carrying a heavy cross over his shoulder. I named him in my head, “Well, that’s Hippie Jesus,” and that’s been a character that has occurred throughout my work ever since. I thought, “Hippie Jesus, that’d be a great idea to use for the Stations of the Cross.” They’ll be bawdy, a little naughty, you know, as it should be, but also trying to be true to the source material.

I had completed three of the stations before Katrina, and I had one unfinished that was upstairs in the loft, so it survived. With all the madness after Katrina, I never got back to it. It’s always bugged me that I never got to finish the Stations. With the residency here in New Orleans, my plan was to get all these models over here to the studio and pose. The problem with that is, everybody that I know works a day job and in the evening most are too tired to be bothered. Modeling is not easy to do. Holding poses is not an easy thing and unless you’re a professional, I might get an hour out of somebody. In an hour, I’m just getting warmed up.

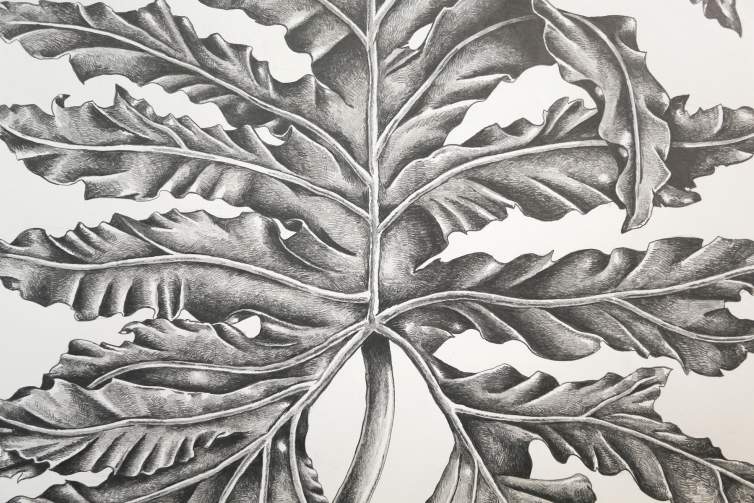

Since I’ve had a hard time getting models, I’ve been working on some small sketches, some new ideas, some characters for the stations, and thinking, what can I be working on besides that? The tropical plants that grow in New Orleans figure a lot into the background of my drawings. I said to myself, “Well, they’re right outside of the studio....” So into the studio come the banana leaves, philodendron, sago palm, Chinese fan palm, elephant ears, etc. I’ve been drawing those because they’re good reference material for later when I'm back in the desert. I’m really enjoying doing them, liking the way they’re turning out.

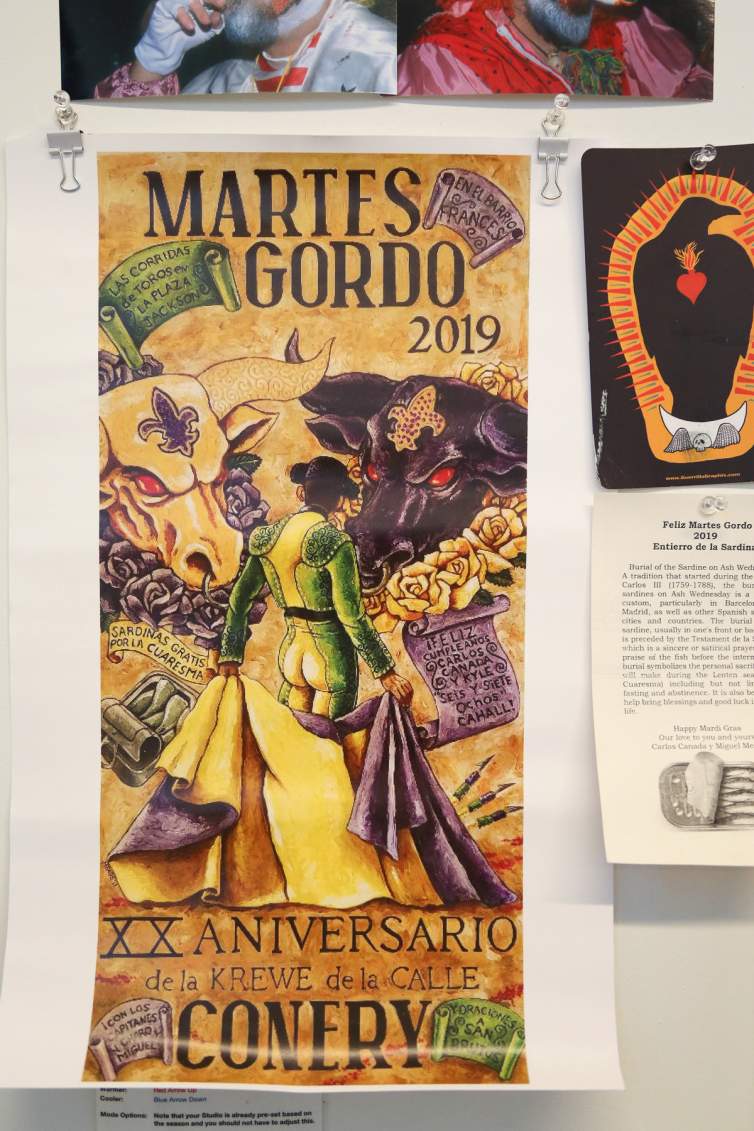

The photos on my studio walls are from past Mardi Gras. The bulls, the masks up there, were from this past year. Our theme this year was the Barcelona bullfights. It was our 20th Mardi Gras. These are all friends of ours in various costumes. Brandon and his wife CC, they’ve started Krewe Divine, which is their filthy tribute to the late performer. They’ve got about 8 or so people that are members now. They go to incredible lengths to get the gowns right and the makeup and hair right. And then you always have the Jesus folks show up to protest. That’s our dear friend Chris, also known as Peggy, with a champagne bottle celebrating in front of all the party poopers... That’s the wonderful Princess Stephanie. This gentleman is from the Skeleton Krewe, and he lives in New York, comes down every year for Mardi Gras, and he always brings just the most amazing masks.

All of this is just a tiny sample of my Mardi Gras photographs. I don’t have a book of my photographs, and that’s something I’d really like to have happen. Finding a publisher is at the top of my to do list.

I had the honor of being asked to do the 2017 Bal Masque poster for the Krewe of Petronius. The Louisiana State Museum at The Presbytère is doing an exhibition about the history of the gay Mardi Gras krewes, which has basically been a hidden history. Wayne Phillips is doing an amazing job of curating it. The exhibition will include my Petronius poster, the painting I did for it, and some sketches. I’m very honored to be in the Louisiana State Museum collection and in this exhibition. The exhibition opens June 6 and runs through 2020.

Getting the Joan Mitchell residency, it’s a great honor. The Foundation has certainly been there for me and Charles in the past. This residency was not expected, and I was very shocked when I got it. The facilities here are top-notch, and the folks here could not be nicer or more accommodating. Artists aren’t known for being the most group oriented, and the staff has worked really hard to get us to hang out, to bond.

The residency has given me access to home [New Orleans] that I don't think that would have happened otherwise, and it’s helping me realize there is a place here for me, that the magic is still here.

To learn more about Michael Meads's work, visit michaelmeads.com.

Interview by Jenny Gill.

Photography by Melissa Dean.